Matthew Angelo Harrison

Proto

Prototypes of the End of a Myth

Kunsthalle Basel, 04.06-26.09.2021

A cold calmness takes over at the threshold of “Proto”, facing the tapered, transparent and minimal sculptures of Matthew Angelo Harrison. Encapsulated in blocks of resin, African spears and masks sit alongside United Auto Workers era union protest gear and other labour equipment. At first sight, the encounter of traditional objects and industrial relics confers an air of a futuristic anthropological museum to the space of the Kunsthalle. Reliefs and engravings on the surfaces of the blocks nevertheless shake the apparent uniqueness of the objects, some of which are even split in two. Their identification is complicated while their symbolism seems to dissolve in the material. The effervescence takes place in the gap between the container (resin) and the contents (objects). “My work unifies contradictions,” states Harrison.1 The African American artist freezes the organic in the synthetic. He preserves yet distorts the original. He imposes the smooth surface on the substance. For his first exhibition in Europe, the past and the present, rituals and industry, the personal and political are not alone in dialogue. The artist proceeds with assemblage and juxtaposition to weave the links between his personal history and the current meaning of current and past conflicts experienced by an entire diaspora.

Photo: Anja Karolina Furrer / Kunsthalle Basel

Since 2016 and his first exhibitions in the United States, he produces sculptures from African objects that he finds. Whether he scans them to print stratified 3D versions of them, or includes them in his work as ready-mades, his gesture evokes the commerce and systems of conserving objects extracted from their original context. Lost in the flux of capitalism, who are the authors? What ancestral history do they convey? Harrison questions their value and “captures” them in polyurethane resin. Forever freezing their evolution, he protects them from further modifications and travel. The transparent yet oppressive armour nevertheless reveals the paradox of this enclosure. His critical view of the trafficking and fetishization of these artefacts– and the delusion of their repatriation?– refers to systems of (over)consumption inherited from colonialism, which, for him, are at the origins of oppression.2 The titles (Vestige of a Disruption; Anopia3) are evidence of the domination he depicts. Entitled Bated Breath, the work with which the exhibition opens, a block containing a Dogon Nommo figure with his hands in the air is reminiscent of recent gestures of submission in the face of the police and George Floyd’s now infamous phrase “I can’t breathe.”

Born in Detroit, American cradle of the auto industry and techno, where he still lives and works, Harrison merges the witnesses of tribal cultures with those of his political and social education for the first time. Having graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2012), he went on to work as a designer for the Ford factories– a common workplace amongst his family, as suggested by the work accessories inherited from his mother such as the jacket in Single Mother (Divided). The violence and intensity of this environment nourished his artistic obsession for technology and the concrete experience of machines. The artist has since developed his own CNC (numerically controlled milling machine) to forge his prototypes. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Harrison does not delegate technical production but rather collaborates with his machines as with real partners in a DIY spirit offering him an autonomy of production (and, indeed, one that is economic). Bordering visibility, the sculpted forms on the resin respond to robot design logic. The traces left by the holes and the curvatures delimit intermediate states, halfway between reality and possibility, inside and outside, according to the artist.

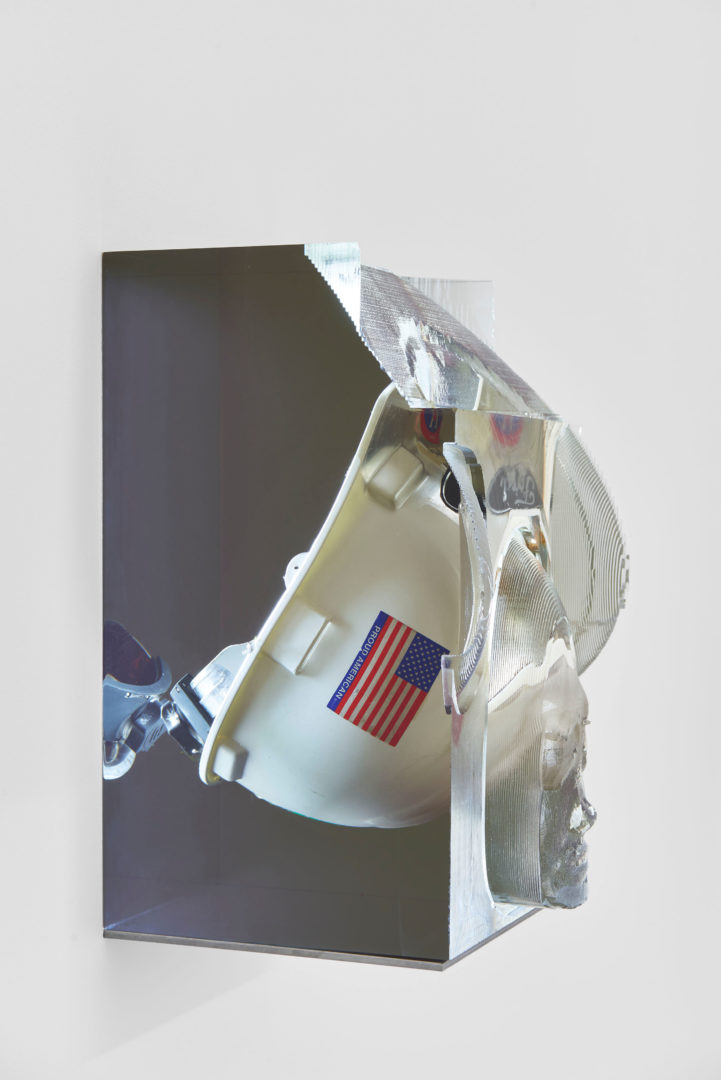

Like the 3D printer (Proto-fountain) around which the exhibition is arranged, the works are hybrids coming straight out of experimentation with technical tools. Each of them is the result of a program conceived by the artist and then executed by the machine. The prototype is the most accomplished model, whose errors can still be observed in order to, a priori, produce a perfectly reproducible version ad infinitum. Composite and experimental, the prototypes developed by Harrison challenge the idea of uniqueness and universal ergonomics. They carry in them traces of chance and hazards promising renewal. Like the image of a (re)birth, Headdress thus synthesizes the approach of “Proto”. The sculpture that reproduces features of a face scanned in low quality at the Penn Museum seems to hatch from a chest in which a construction helmet is also embedded. The oracle-like cyborg creature marries the curves of the object it has digested. Serene and turned towards the future, it exists through the assimilation of times and objects.

The non-linear lines and variations drawn by the arrangement of the works in the space outline the precise and punctuated movements of the 3D printers and tools of mass production. The void left by the stems of the bases responds to the transparency of the blocks. Soberly designed, the metal structures realised by the artist are an integral part of the work. Their clear yet austere lines punctuate the space, recalling other manifestations of control– such as those imposed by modernism and the power of the form.4 The conjugation of cultural and working class histories reflect the repetition of exploitative systems and the precariousness born from the intertwined systems of capitalism and colonialism. In resistance to these mechanisms, Harrison’s political and aesthetic connections articulate some of the strengths of Blackness, as theorised by philosopher and poet Fred Moten, “That blackness is generation’s more-than-arbitrary name; that she is our more-and-less than single being.”5 Blackness is a generational legacy, a relational network whose links gathered then integrated in the present by the machine and for the future seem to finally carry the hope of the end of the American exceptionalism.

- Interview with Grant Johnson, Artforum, 30 June 2019.

- See The Economic History of Capitalism, Leigh Gardner and Tirtankhar Roy, Bristol University Press, 2020

- Anopia refers to being blind due to a physical defect or the absence of an eye.

- Harrison often quotes Adolf Loos, author of Ornament and Crime (1908) whose rationalist and functionalist arguments at the origin of the modernist movement are accompanied by racist and sexist comments.

- Fred Moten, Stolen Life, Consent Not to be Seing, Duke University Press, 2018.

Image on top : Matthew Angelo Harrison, vue de l’installation/installation view, Proto, Kunsthalle Basel, 2021, vue sur/view on, Bated Breath, 2021. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

- From the issue: 98

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Marc-Camille Chaimowicz at Wiels , Lucy Raven, Hanne Lippard, Florence Jung, Camille Picquot,

Related articles

Performa Biennial, NYC

by Caroline Ferreira

Camille Llobet

by Guillaume Lasserre

Thomias Radin

by Caroline Ferreira