The Promise of Total Automation

Kunsthalle Wien, 11.3_29.05.2016

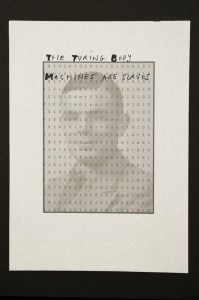

Henrik Olesen, how do i make myself a body? (Detail), 2008-2016. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York © Henrik Olesen.

The first industrial revolution, which saw the gradual development of new plans for incorporating the human element in the process of producing goods, has been followed by a second and then a third revolution, which have seen the introduction into the manufacture of industrial products of more and more increasingly intelligent machines, which have increasingly taken on tasks hitherto allotted just to man’s skills. As the world of labour has gradually relieved working people of arduous and repetitive jobs by proceeding to a massive automation of the industrial and manufacturing sector, society as a whole has been pursuing its race towards its modernist ideal of dominating nature, with a significant part being played by its belief in technology as a vehicle of social progress. At the end of the 20th century, the computer revolution, whose impact we are still in the process of gauging, brought in new transformations in the organization of labour, by way of many different kinds of re-organization, dematerialization, relocation, and the like, although it is impossible to say whether it has given working people more time by relieving them of boring and repetitive tasks, or whether, on the contrary, it has made them more dependent on that ubiquitous tool called the computer. This belief in technical progress associated with an improvement in living conditions for both workers and the populace as a whole—that unwitting pact which, in western societies, created a link between the middle classes and the ruling classes—has slowly eroded over the past few decades with the revelation that a small élite has harvested the dividends of this progress, at the same time as the modernist ideal of having dominance over an objectivized nature was called into question by the growing awareness of the bonds which render the fate of humanity one with the fate of nature. During those same decades, liberating ways of thinking with regard to the consumer society, which have come in the wake of movements such as the May ’68 riots, have developed towards more subtle stances with regard to objects: this relation is now proceeding by way of a mixture of assumed desire combined with a consciousness of the disastrous consequences of industrial over-production for, on the one hand, planet earth, and, on the other, for the populations of the “South”.

Magali Reus, Leaves (Amber Line, May); Leaves (Harp January), 2015, Courtesy Magali Reus, The Approach, London and Rubell Family Collection. Vue de l’exposition : The Promise of Total Automation, Kunsthalle Wien 2016, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff.

The seductiveness of merchandise to which Marx refers in The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof is seen from a new angle: the position of a philosopher like Simondon, who is widely referred to in the statement accompanying the exhibition on view at Kunsthalle Wien, describes this shift in the relation to the object which transforms it by re-questioning it. The thinking of this philosopher, who is especially concerned with issues connected with the technical object, finds a new extension with the advent of connected objects, the latest consequence of the technological advances which make these latter less and less inert things and more and more active and reactive things, extensions rather than prostheses, which inform us and influence us in return, taking an ever more profound part in the constitution of the contemporary subject.

Melanie Gilligan, The Common Sense, 2015. Photo : Stephan Wycko. Courtesy Melanie Gilligan ; Galerie Max Mayer, Düsseldorf.

It is on such a philosophical base that the concept of “The Promise of Total Automation” is founded—this being the watchword of Fordism, whose influence on modern society went well beyond a mere rationalization of production procedures in industry. The exhibition diversifies the viewpoints, but without ever totally toppling either into an extreme form of pessimism or into an ingenuous idealism, by increasing the number of references to the past, with, for example, the presence of period machines like so many forerunners of the total automation in the offing: so it was with the Jacquard loom, which lay at the root of both the first programmable machines and of binary codes, and thus, in a way, of computer science in its entirety. Also on view are a device designed to send signals in Morse code, which itself also revolutionized the world of telecommunications, and this early so-called “portable” PC model which barely fits into two large suitcases and which, compared to our present-day laptop computers, resembles something laughably old-fashioned, even if it is barely thirty years old, grazing, in passing, the cult of the latest technological trend, and illustrating the increasing acceleration of the obsolescence of things. In this same vein, the curator Anne Faucheret deploys a whole arsenal of artistic stances denouncing the idealization of technological novelty which usually stems from a mercantile ideology: so Nick Lessing’s machines designed to produce free energy have seen their development systematically impeded by energy producers who are not particularly seeking to apply such liberating procedures. Tyler Coburn’s piece, a 3D print of a common-or-garden clog—sabot, in French, giving sabotage—refers to French workers’ gestures of resistance as they tossed their clogs inside machines, to destroy them, and thus protest against the disappearance of their traditional work tools. The Bureau d’Etudes posters which, with a wealth of detail, describe the production routes of certain items, as well as information which often remains hidden, act, for their part, like nothing less than accusations against the machinations of rarely virtuous manufacturers.

Julien Prévieux’s work titled What shall we do next? seems to be telling us that the promise of a state of total automation is being conveyed above all by the threat of a total destruction of the last pockets of resistance to the gung-ho predatory activities of capitalism, because even simple gestures—the most personal and inalienable features of the individual—are likely to be “labeled”. The artist has appropriated these latter—to which particular attention is paid by industry, being necessary, as they are, for the manipulation of these countless new gadgets regularly arriving on the market—in order to create a particularly sophisticated and stylish choreography. In a way, this work is ambiguous because, by aestheticizing what may turn out to be dangerous for the potential user-consumers that we are, it makes a metaphor of a situation of alienation which is repeated ad infinitum, and which conveys the capacity of capital to stage the hijacking of the public good, so as to make it thoroughly unmanageable by the masses. Melanie Gilligan’s video The Common Sense (2015), which borrows the codes of hit TV series in order to import them into the high-tech industrial world, is part and parcel of this selfsame both critical and deceptive vision of the “fine promise”.

Cécile B. Evans, How Happy a Thing Can Be, 2014. Videostill.

Courtesy Radar/LUA, Wysing Arts Center, Cambridge. © Cécile B. Evans.

Pushing the logic of automation to extremes, artists like Cécile B. Evans and Thomas Bayrle imagine worlds where objects would from now on evolve on their own account, independently of their creator’s control: these scenarios, which until very recently seemed only to exist in the imaginations of science-fiction authors like J.G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick, are today finding increasingly plausible updated versions, as with Google cars, for example. The exhibition does not deal with this kind of catastrophic and dystopian scenario, which it was perhaps legitimate to envisage in the logical extension of the meaning of the Fordian formula, for if we do push it right into a corner, we end up with an Isaac Asimov-like world, filled with androids and humans whose survival is in danger…. Instead, the curator has imagined a slightly more zany response by presenting Harry Dodge’s clown-like robots, in an attempt to offset the solemnity which emanates from certain works, one such being James Benning’s, which deals with the tale of Ted Kaczynski: the video refers to the world of the guy who was better known as the Unabomber, whose curses were aimed at that élite we mentioned earlier, the one which has seen fit to collect the dividends of those famous technological advances.

Lastly, and somewhat unexpectedly, paintings have a not inconsiderable place in the show, first and foremost those produced by Konrad Klapheck, which slightly call Fernand Léger to mind in his celebration of the machine, which he depicts in a literal and exhilarating way, but also the paintings of Peter Halley who, in his flashy and clear-cut way of mixing smooth flat tints with his famous roughcast, radically incarnates a spare abstraction that is totally self-absorbed. This latter artist’s paintings in fact make us think of printed circuits and computer chips with their radical diagrams, and their pithy if superficial seductiveness, which certainly calls to mind the bare but no less brightly coloured organs of Magali Reus’s bachelor machines.

Curated by: Anne Faucheret

With: Athanasios Argianas, Zbyněk Baladrán, Thomas Bayrle, James Benning, Bureau d’études, Steven Claydon, Tyler Coburn, Philippe Decrauzat & Alan Licht, Harry Dodge, Juan Downey, Cécile B. Evans, Judith Fegerl, Melanie Gilligan, Peter Halley, Channa Horwitz, Geumhyung Jeong, David Jourdan, Barbara Kapusta, Konrad Klapheck, Běla Kolářová, Nick Laessing, Mark Leckey, Tobias Madison & Emanuel Rossetti, Benoît Maire, Mark Manders, Daria Martin, Shawn Maximo, Régis Mayot, Wesley Meuris, Gerald Nestler, Henrik Olesen, Julien Prévieux, Magali Reus.

- From the issue: 78

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Hilma af Klint, Playground, Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum,

Related articles

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez