Wolfgang Tillmans

“What Is Different?”, Carré d’art, Nîmes (F), 4.05 — 16.09.2018

The Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition at the Carré d’art in Nîmes is part of a series of solo shows being held in famous institutions like the Tate Gallery and the Beyeler Foundation. “What Is Different?” is not a departure from the artist’s recurrent concerns which mix questions connected solely with the medium with socio-political matters. Style and content: the treatment of the image by way of the latest technological breakthroughs goes hand-in-hand with an extreme attention paid to issues informing the societal and political debate of the moment. The formal innovation which earned the Berlin artist early recognition—in 2002 a large solo show at the Palais de Tokyo (Vue d’en haut) enabled the Paris public to discover his unframed digital prints which were simply affixed to the walls using small clips—is still a tool in his quest for a reality which he seems to hunt down in the smallest of nooks and crannies: the use of ever more efficient printers always asserts the same demand, only the format seems to have varied, as well as the pixel density. At the same time, his political positions, in which are expressed the significance of a culture imbued with post-utopia and clubbing, do not falter…

The images he distills in Nîmes, in what he calls the “cabinet”, crudely display his sexual preferences, but without toppling over into gratuitous provocation; Tillmans exhibits and exhibits himself with neither complexes nor anxieties in the bosom of an open European society freed of its religious straitjackets and other behavioural prohibitions, but a society that is nevertheless threatened by the comeback of reactionaries, in force. In the publication accompanying the exhibition, for which he is the guest editor-in-chief—Sternberg Press’Jahresring, which is nothing less than an institution now—the photographer tries to shed light on what has enabled the re-emergence of negative energies in a Germany whose economic health is brazen, and, beyond just Germany, on what is threatening one of the pillars of European cohesion, the acceptance of “non-standardized” forms of behaviour. He offers himself the luxury of doing a tour of the ministers in the outgoing government coalition, and questioning, after Sigmar Gabriel, a figure like Wolfgang Schaüble who, as we easily guess, does not share the same political ideas but shows himself to be surprisingly lucid when it comes to determining the causes behind this disappearance of the taboos which have hitherto managed to curb the comeback of anti-Semitism and populism.

Another of the artist’s major preoccupations is the phenomenon of the backfire effect which consists not only in adopting viewpoints contradicted by the facts, but, in addition, involves defending them tooth and nail against all manner of rationality: thriving in the loam of a growing disinterest in reasoned information, and of wholesale disinformation upheld by lobbies, the backfire factor has a bright future ahead of it. The famous fake news which, during the Trump campaign, chalked up nothing less than a turning-point, is the correlate of this crafty psychological principle, but, when all is said and done, it is merely part and parcel of a lengthy tradition of mind manipulation, somewhere between the invention of “weapons of mass destruction” by the Bush administration and the spiriting away of secret files about the Vietnam war by Nixon. It is easy to see that these subjects considerably exercise an artist who is unable to remain indifferent to anything that involves the production of contemporary imagery; the very distinctive presence of headlines at the beginning of the stroll betrays a never denied interest in the press, and in newspapers in particular. What is the photographic image made of if not many different manipulations and other interventions on its raw material, which is reality? A photo is never really pure and is always part of a discourse, a desire for interpretation, or even an ideology.

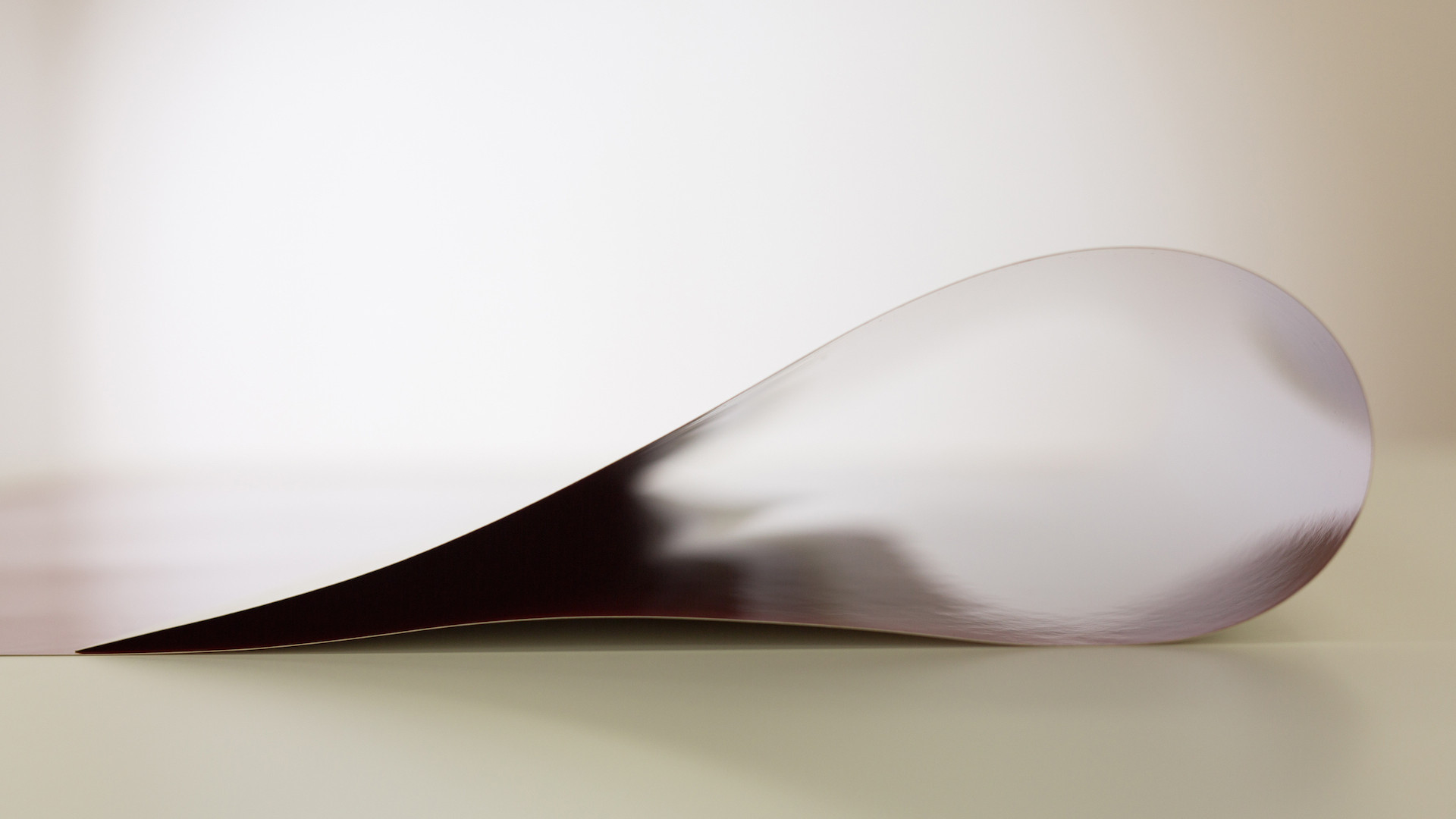

In the first exhibition room, a set of twinned display stands are placed opposite one another, one showing insignificant objects—stones, potatoes, and pebbles—while the other exhibits its photographic double: these works, which are disarming in their simplicity and effectiveness, refer to the chasm which separates reality from its representation. The artist’s self-portraits are also very present and remain one of the major themes of his work: one of the very earliest, dating from the 1980s, is also on view, a fact that is sufficiently rare to be worth mentioning. The shrewdly organized circuit lets visitors discover the organic nature of a praxis which encompasses the entire spectrum of contemporary photography. The central moment of the show is undoubtedly the large room where countless portraits of every colour and format rub shoulders, mingled with very alive still lifes of plants, trees and various objects in an ever renewed attempt to broach the complexity of the world but also to assert obvious peer principles. The large compositions/collages from the artist’s latest series, displaying enigmatic slogans and sentences, attest to the difficulty of representing a world which slips away from the camera’s sole “objectivity”. The last room in the exhibition winds up a far-reaching line of thinking about the medium with a series titled paper drop, which represents something akin to a return to the object and the thing, removing us from a photographic realism which we had hitherto become accustomed to.

(Image on top: paper drop Oranienplatz, a-d, 2017)

- From the issue: 86

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Hilma af Klint, Playground, Lyon Biennial, Anozero' 24, Coimbra Biennal, Signs and Objects. Pop art from the Guggenheim Collection at Guggenheim Museum,

Related articles

Ho Tzu Nyen

by Gabriela Anco

Hilma af Klint

by Patrice Joly

Plaza Foundation

by Andrea Rodriguez