Signer/Contresigner

Signer/Contresigner

Contexte et notes sur la copie chez Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince et Cindy Sherman

Please scroll down for english version

« Découvrir le corps de la Zambinella, c’est donc faire cesser l’infini des codes, trouver enfin l’origine (l’original) des copies, fixer le départ de la culture, assigner aux performances leur supplément (« plus qu’une femme ») (…) ».

Roland Barthes, « Le Chef d’œuvre », dans S/Z, 1970.

1968. Robert Morris et Stan VanDerBeek inséraient dans le numéro 5/6 de la revue Aspen une copie en film Super 8 de leur performance Site réalisée en 1964. Morris déplaçait un premier panneau rectangulaire, puis un second, découvrant une femme nue, étendue, la main gauche posée sur son entrejambe, la droite posée sur un coussin. Un ruban noir serré autour de son cou, le regard fixe et dressé, plus de doute, la référence de Site était l’Olympia de Manet. Moins qu’une copie, l’Olympia se faisait ici référence intégrée dans une performance, assurant le rôle d’un contrepoint historiquement déterminé à la chorégraphie qu’opérait Morris dans son environnement – ces diverses mises en situation des panneaux qui initialement obturaient la vue de l’Olympia.

1874. Lors de la première exposition des impressionnistes, Cézanne exposait sa seconde version d’Une Moderne Olympia. Même s’il gardait du prototype la structure générique, il proposait là une citation aménagée et adaptée de l’œuvre. Comme par excès de littéralité, il insérait le personnage absent du tableau de Manet, le visiteur de la prostituée prenant l’apparence du peintre lui-même. Cézanne donnait de la sorte une des clés de lecture de l’œuvre de Manet. D’une œuvre dont la violence et l’ambiguïté de l’effet relevaient, plus que de la nudité plate de la prostituée, de la logique inclusive du spectateur soutenue par ce double jeu de regards – celui frontal de l’Olympia, celui surpris et naturel du chat –, Cézanne en révélait platement et sans ambiguïté aucune le fonctionnement.

#1. Sherrie Levine. Histoire de l’art

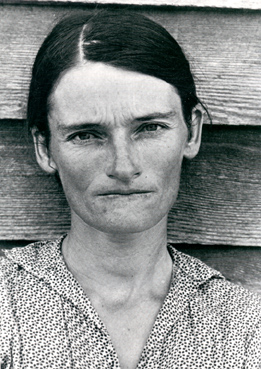

Sherrie Levine contresigne l’histoire de l’art. En 1981, elle réalise plusieurs séries de photographies situées après, dont celle intitulée After Walker Evans. Celles-ci consistent en la reproduction à l’identique de photographies tirées initialement par le photographe américain dans le cadre de la Farm Security Association. Précision photographique, entre la copie et l’original, pas une infime différence. On y retrouve les mêmes personnages, les mêmes regards, les mêmes contrastes. Mais d’un geste à l’autre, entre la version d’Evans et celle de Levine, s’inscrit une infime différence venant questionner les critères de l’unique et de l’originalité. Cette identité n’en élimine en effet pas leur singularité. Elles répondent à des intentions et des contextes différents. (Pour faire bref, Evans interroge la copie d’une réalité sociale et le regard que l’on y porte, Levine interroge la copie d’une réalité culturelle et le regard que l’on y porte). Entre ces deux images se produit un intervalle scindant leur apparente identité et questionnant leur sens. Toute répétition est source de différence dirait Levine. Paraphrasant Barthes, elle indiquait également : « La naissance du regardeur est au prix de la mort du peintre » (). C’est dans le retrait du peintre que naît le regardeur d’une œuvre, Levine soulignant par ce geste qu’au-delà de la signature inaugurale d’Evans et de sa contresignature est nécessairement impliquée notre contresignature par l’exercice d’une lecture réfléchissant (sur) ces copies du réel.

L’histoire ne s’arrête pas là. Rétrospectivement, l’Olympia se décline avec David, Cabanel, Titien, etc. Après, elle se déclinera avec Picasso, Dubuffet, Twombly, Rivers, etc. Entre Morris et Cézanne, l’adresse à Manet est différente et avec elle, le statut de la copie et de l’appropriation. L’intention avouée de Cézanne était d’opérer une entreprise de modernisation de l’Olympia : en adaptant son code iconographique, par l’intégration de ce spectateur absent de l’œuvre de Manet ; en adaptant son code matériel, au moyen d’un effet d’esquisse que décrivait Baudelaire dans Le Peintre de la vie moderne. Cézanne copie et s’approprie. Et cette appropriation vise à ce que l’œuvre produite (Une Moderne) se substitue à l’original (Olympia), une opération invalidant du même coup la modernité précédente du code de l’Olympia. La référence à Manet dans Site de Morris ne serait quant à elle pas réductible à cette opération d’une modernisation/substitution, Morris déplaçant ici le code de l’Olympia dans la sphère de sa performance, déplacement produisant une circulation et une reconfiguration du sens de l’œuvre, en ce lieu (Site). Schématiquement, l’opération de Cézanne renverrait à celle de la modernité, et par extension à celle du modernisme, selon une conception restrictive et rapide de ce terme, où les œuvres se substituent et s’invalident les unes après les autres. L’opération de Morris renverrait quant à elle, selon une conception tout aussi rapide et restrictive, à celle du postmodernisme, où la modernité des œuvres précédentes, « réduites » au statut d’image-document, se trouve potentiellement engagée dans un champ discursif ramifié qui ne cesse de s’actualiser (). À l’œuvre prétendue autonome du modernisme se substituerait (cette substitution est au centre même du paradoxe concernant cette coupure) l’œuvre désautonomisée du postmodernisme, incluant dans son épaisseur ce tissu de référence ; l’œuvre trouvant dès lors sa singularité et sa pertinence (plus que son originalité) dans la manière dont elle aménage et produit ses relations entre ces copies, références, citations.

#2. Richard Prince. Culture

En 1983, Prince écrivait dans Why I Go to the Movies Alone : « Ils [il faut lire ici un il au singulier, l’auteur] accrochent les photographies de Pollock à côté de cette nouvelle “sorte” de posters qu’ils viennent juste d’acheter. Ces posters venaient de sortir. C’étaient des agrandissements en noir et blanc… d’au moins 70 centimètres sur 100. En extraire un de l’ensemble leur donnait le sentiment de réaliser quelque chose que tout nouvel artiste se devait de faire » (). Figure clé de l’héroïsme du modernisme, Pollock se trouve ici réduit à ces posters standardisant dans leurs forme et contenu une image de l’artiste diffusée à x exemplaires, tel le produit d’une culture partageable et accessible à tous. À la même période, Prince re-photographiait des images publiées dans des magazines. Première opération, se mettre en retrait, toute substance imagée, déjà reproduite et extraite de la culture, peut être le point de départ d’une œuvre d’art. Untitled (three women looking in the same direction) représente trois femmes différentes, cadrées plus ou moins de la même manière et regardant dans la même direction, non pas vers le spectateur mais quasi vers l’arrière, le regard jeté au-dessus de leur épaule. Deuxième opération, neutraliser les codes visibles de la culture qui produit ces images : aucun texte donc aucun lien avec un contenu directement identifiable (scène de film ou publicité par exemple) ; privilégier les plans moyens afin de cadrer suffisamment le sujet sans en accentuer la présence ; bref, des moyens venant redoubler la mise à distance de l’opération re-photographique. Trois femmes, trois regards, trois images, trois copies qui paradoxalement, dans la réflexion de notre regard, n’en retrouvent pas moins, à un moment ou un autre, une valeur d’original dont la trame préserve, même de manière indicielle, son ancrage culturel.

Dans son article « La Sculpture dans le champ élargi », Rosalind Krauss indiquait qu’à la logique autonomiste du modernisme faisait place une logique où l’économie de la copie allait jouer un rôle déterminant, l’espace de la peinture demandant à être interrogé par une expansion de son champ réalisée à partir de l’opposition unicité/reproductibilité (). Plus précisément, le rapport à l’image (plus qu’à la peinture) instauré dans les pratiques de différents artistes dès la seconde moitié des années 1960 aux années 1970 viennent mettre en tension la question de l’originalité et de l’unicité telle qu’elle put s’exprimer dans le discours moderniste (formaliste) de Clement Greenberg et dans celui (existentialiste) d’Harold Rosenberg. Dans la logique greenbergienne, c’est en effet la qualité de la conception qui équivalait à la signature de l’originalité de l’artiste. Pour Rosenberg, c’est l’intensité de l’action inscrite sur la surface de la toile qui équivalait à cette même signature. Dans cette perspective, ce travail de sape de l’unique et de l’original au profit du reproductible, entamé par l’art minimal et conceptuel, put trouver, par un phénomène de contre-coup historique, légitimation et objet de réflexion dans le ready-made de Marcel Duchamp. Produit standardisé, copie de copie d’un original à jamais absent ou désormais perdu, le ready-made avait comme effet de suspendre, temporairement, tout privilège de la signature. Mais c’est également par le travail entamé par les artistes proto-pop et pop que ces pratiques purent trouver un objet de réflexion, particulièrement avec Robert Rauschenberg. Pour ne donner qu’un exemple, Factum I et Factum II (1957) problématise cette question de la signature, cette double œuvre consistant en la reproduction, quasi à l’identique, des mêmes motifs, des mêmes coulées de peintures, des mêmes gestes ; cette répétition d’un simulacre du même produisant de la sorte une inévitable scission de l’origine, chacune étant tour à tour copie de l’une et de l’autre. Rauschenberg consomme le passage de la peinture vers l’image (et il n’est nullement ici question de déclin). Un passage qui trouvera à s’exprimer par la Picture Generation tirant son nom de l’exposition que Douglas Crimp organisa pour à New York en 1977. S’y trouvaient rassemblés des artistes tels que Troy Brauntuch, Jock Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo et Philip Smith, des artistes dont les pratiques selon Crimp ne rencontraient en rien le modèle moderniste que s’était essayé à définir Greenberg et ensuite Michael Fried. Travaillant entre peinture et sculpture, ils développaient une pratique de l’image où la question de la re-présentation s’avérait être centrale, avec elle celle de copie et de l’appropriation. Comme Crimp l’écrivait ailleurs, au sujet de Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince et de Cindy Sherman, trois artistes dont la pratique se développait à cette période autour de cette question de la copie et de l’appropriation des codes de l’histoire de l’art, de la culture et de la fiction : « Leurs images sont dérobées, confisquées, appropriées, volées. Dans leur travail, l’original ne peut être situé, il est toujours différé ; même l’original se révèle être une copie » ().

#3. Cindy Sherman. Fiction

La série est connue. Untitled Film Still consiste en plusieurs dizaines de photographies de petites dimensions. Pour chacune, une femme, un contexte différent. Dans l’une (plan large), elle est étendue sur un drap noir, simplement vêtue d’une chemise, un bouquin ouvert face couverture. Dans une autre (contre-plongée), décor de ville américaine en arrière-plan, habillée d’un tailleur, coiffée d’un chapeau, elle regarde en oblique du cadre. Dans une autre encore (plongée), accroupie en face d’une cuisinière, elle semble surprise par l’entrée d’un tiers, faisant mine de ramasser les produits étalés au sol après que le sac les contenant se fut déchiré. Cette femme, on le sait c’est Cindy Sherman jouant là avec les codes de la fiction. Aucune de ces photographies n’est la réplique d’une image extraite d’un film ou d’une publicité. Elles n’en sont que des reconstructions (c’est-à-dire plus ou moins que des copies, des simulacres) selon une opération faisant appel à notre mémoire des codes ici mis en fiction. Alors que chez Prince et Levine la présence de l’artiste était chaque fois mise à distance, différant de la sorte sa signature au privilège d’une contresignature, chez Sherman, sa présence se trouve littéralement investie dans l’image. Pourtant, chaque image présente une autre image de l’artiste, cette présence prenant de la sorte la forme d’une somme irréductible d’identités différentes : celle de la pin-up étendue, celle de la ménagère surprise, celle d’une femme dans le contexte banal d’une ville. Question d’origine. Question d’identité. À partir de ces fictions d’un film, jamais là et qui ne viendra jamais, à nous de reconstruire une narration, combler, si cette tâche s’avère possible, l’intervalle vacant entre ces différentes images.

« Ainsi le réalisme (bien mal nommé, en tout cas souvent mal interprété) consiste non à copier le réel, mais à copier une copie (peinte) du réel […]. C’est pourquoi le réalisme ne peut être dit “copieur” mais plutôt “pasticheur” (par une mimésis seconde, il copie ce qui est déjà copié ».

Roland Barthes, « Le Modèle de la peinture », dans S/Z, 1970.

Sign/Countersign

Context and notes on the copy in the work of Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman

Raphaël Pirenne

“Discovering the body of La Zambinella, thus means putting a stop to the endless codes, finally finding the origin (the original) of the copies, fixing the departure of culture, and assigning supplements to performances (“more than a woman”) […]”.

Roland Barthes, “Le Chef d’oeuvre” in S/Z, 1970

1968. Robert Morris and Stan VanDerBeek inserted in issue no. 5/6 of the magazine Aspen a super-8 film copy of their performance Site put on in 1964. Morris moved a first rectangular panel, then a second, discovering a naked woman, lying there with her left hand resting on her groin and her right laid on a cushion. With a tight red ribbon around her neck, and her gaze staring and straight, there could no longer be any doubt that the reference for Site was Manet’s Olympia. Less than a copy, Olympia here became a reference incorporated in a performance, providing the role of a historically determined counterpoint to the choreography executed by Morris in his environment—those different situations of the panels which initially blocked the view of Olympia.

1874. During the first Impressionists’ exhibition, Cézanne showed his second version of Une Moderne Olympia. Even if he kept the overall structure of the prototype, he proposed therein a reference befitting and adapted to the work. As if through an excess of literalness, he slipped in the character missing from Manet’s picture, the visitor to the prostitute taking on the appearance of the painter himself. In a work whose violence and ambiguity stemmed, not so muh from the prostitute’s flat nakedness, as from the inclusive logic of the viewer underpinned by this double interplay of gazes– the frontal state of Olympia herself, and the surprised and natural look on the cat’s face—Cézanne revealed the way itfunctioned in a flat way, with absolutely no ambiguity.

#1Sherrie Levine. History of art

Sherrie Levine countersigns the history of art. In 1981, she made several series of photographs coming after, including the one titled After Walker Evans. These consisted in the identical reproduction of photographs initially printed by the American photographer for the Farm Security Association. Photographic precision, between copy and original, not the tiniest difference. In them we find the same characters, the same looks and gazes, the same contrasts. But from one gesture to the next, between Evans’s version and Levine’s, there is a tiny difference that challenges the criteria of uniqueness and originality. This identity does not in fact do away with their singularity. They respond to different intentions and contexts. (To cut a long story short, Evans questions the copy of a social reality and the way we look at it. Levine questions the copy of a cultural reality and the way we look at it). Between these two images there’s an interval which splits their apparent identity and questions their meaning. All repetition is a source of difference, Levine would say. In paraphrasing Barthes, she also pointed this out: “…the birth of the onlooker comes at the price of the death of thepainter”.i It is in the withdrawal of the painter that the viewer of a work is born, and Levine underscores through this gesture that beyond Evans’s inaugural signature and his counter-signature, our own counter-signature is perforce involved by the exercise of a reading reflecting these copies of the real.

The story does not stop here. With hindsight, Olympia goes hand in hand with David, Cabanel, Titian, and so on. Afterwards, it would go hand in hand with Picasso, Dubuffet, Twombly, Rivers and the like. Between Morris and Cézanne, the address to Manet is different and with it, the status of the copy and appropriation. Cézanne’s avowed intent was to effect an undertaking that would modernize Olympia: in adapting his illustrative code, by incorporating this onlooker absent from Manet’s work; in adapting his material code, by means of a sketch-like effect which was described by Baudelaire in Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne. Cézanne copies and appropriates. And this appropriation is aimed at the work produced (Une Moderne) replacing the original (Olympia), an operation invalidating by the same token the precious modernity of the code of Olympia. Thee reference to Manet in Morris’sSite, for its part, cannot be scaled back to this operation involving a modernization/substitution, with Morris here shifting the code of Olympia into the realm of his performance, a shift producing a circulation and a reconfiguration of the sense of the work, in this place (Site). Schematically speaking,Cézanne’s operation would refer to that of modernity, and by extension to that of modernism, based on a rapid and restrictive conception of this term, where works replace each other and are invalidated, one after the other. Morris’s operation, for its part, would refer, based on a no less rapid and restrictive conception, to that of postmodernism, where the modernity of the previous works, “reduced” to the status of image-document, is potentially caught up in a ramified discursive field which is forever being updatedii. The allegedly autonomous work of modernism would be replaced (this replacement lies at the very hubof the paradox involving this break) by the de-autonomized work of postmodernism, including in its depth this fabric of reference; the work henceforth finding its singularity and its relevance more than its originality) in the way in which it arranges and produces its relations between these copies, references and quotations.

#2 Richard Prince. Culture

In 1983, Prince wrote in Why I Go to the Movies Alone: “They [instead of ‘ils’ you should read ‘il’, i.e. he, not they: the author]affix the Pollock photographs alongside this new “sort” of poster which they have just bought. These posters had just come out. They were black and white enlargements… at least 70 centimetres by 100. Taking one from the whole set gave them the feeling of making something that any new artists should do”iii. As a key figure of the heroism of modernism, Pollock is here reduced to these posters which, in both style and content, standardize an image of the artist distributed in x number of copies, like the product of a shareable culture, accessible to one and all. In the same period, Prince re-photographed pictures published in magazines. First operation,step back, all pictorial substance, already reproduced and extricated from culture, can be the point of departure for an artwork. Untitled (three women looking in the same direction) depicts three different women, framed in more or less the same way and looking in the same direction, not towards the onlooker but almost backward, their gaze cast over their shoulder, Second operation, neutralize the visible codes of the culture producing these images: no text, therefore, no link with any directly identifiable content (film scene or advertisement, for example); showing a preference for medium shots so as to sufficiently frame the subject without emphasizing its presence; in a word, methods bolstering the distance of the re-photographic operation. Three women, three gazes, three images, three copies which, paradoxically, in the reflection of our eye, still find, at one moment or another, the value of an original whose subject preserves its cultural mooring, even in an indicative way.

In her article “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, Rosalind Krauss suggested that the autonomist logic of modernism was giving way to a logic where the economy of the copy would play a decisive role, with the space of the painting asking to be questioned by an expansion of its field based on the uniqueness/reproducibility contrastiv. More precisely, the relation to the image (more than to the painting) introduced into the praxes of different artists between the latter half of the 1960s and the 1970s creates a tension with the issue of originality and uniqueness, as it could be expressed in the modernist (formalist) discourse ofClement Greenberg and in the (existentialist) discourse of Harold Rosenberg. In the Greenbergian logic, it is in fact the quality of the conception which equalled the artist’s signature of originality. For Rosenberg, it is the intensity of the action inscribed on the canvas’s surface which equalled that same signature. In this light, this work of undermining the unique and the original in favour of the reproducible, ushered in by Minimal and Conceptual art, could find, through a phenomenon of historical repercussion, both legitimization and object of reflection in Marcel Duchamp’s readymade. As a standardized product, copy of a copy of an original invariably absent or now lost, the effect of the readymade was to suspend, temporarily, all privilege of signature. But it is also through the work embarked upon by the proto-pop and pop artists that these praxes could find an object of reflection, especially with Robert Rauschenberg. To give just one example, Factum I and Factum II of 1957 deal with the issue of this matter of the signature, this double work consisting in the almost identical reproduction of the same motifs, of the same runs of paint, of the same gestures; this repetition of a simulacrum of the same producing accordingly an inevitable split from the origin, each one being turn by turn a copy of the one and the other. Rauschenberg consummates the shift from painting to image (and here there is no question of decline). A shift which would end up being expressed by the Picture Generation deriving its name from the show which Douglas Crimp organized for Artists Space in New York in 1977. In it were brought together artists like Troy Brauntuch, Jock Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo and Philip Smith, artists whose activities, according to Crimp, in no way encountered the modernist model which Greenberg and then Michael Fried had tried to define. Working between painting and sculpture, they developed a praxis of the image where the issue of re-presentation turned out to be central, and with it the issue of copy and appropriation. As Crimp wrote, moreover, about Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman, three artists whose praxis was being developed in that period around this issue of the copy and the appropriation of the codes of art history, culture and fiction: “Their images are hidden, confiscated, appropriated, stolen. In their work, the original cannot be situated, it is invariably deferred; even the original turns out to be a copy.”v

#3 Cindy Sherman. Fiction

The series is well known. Untitled Film Still consists in several dozen small photographs. For each one, a woman, a different context. In one (wide shot), she is prone on a black sheet, wearing just a shirt, with a book open showing the cover. In another (low angle shot), with the décor of an American city in the background, wearing a suit, and a hat, she looks aslant from the frame. In yet another (high angle), crouching by a stove, she seems surprised by the entrance of a third person, pretending to pick up the products spread on the floor after the bag holding them tore open. We know that this woman is Cindy Sherman playing with the codes of fiction. None of these photographs is the replica of an image taken from a film or commercial. They are just reconstructions (i.e. more or less just copies, simulacra), based on an operation calling for us to remember the codes here fictionalized. Whereas with Prince and Levine the presence of the artist was each time put at a distance, thus deferring the signature in favour of a counter-signature, with Sherman, her presence is literally invested in the image. But each image presents another image of the artist, this presence thus taking the form of an irreducible sum of different identities: that of the prostrate pin-up, that of the surprised housewife, that of a woman in the common-or-garden setting of a city. Matter of origin. Matter of identity. Based on these fictions of a film, never here, and never coming, it is up to us to reconstruct a narrative, and, if this task seems possible, fill in the vacant gap between these different images.

“So realism (ill named, in any event poorly interpreted) consists not in copying the real, but in copying a (painted) copy of the real […]. This is why realism cannot be called a “copier” but rathera “pasticher” (through a second mimesis, it copies what is already copied”

Roland Barthes, “Le modèle de la peinture” in S/Z, 1970.

Notes:

i Howard Singerman, “Sherrie Levine’s Art History”, in October, vol. 101, Summer 2002, pp. 96-121.

ii See Roland Barthes, “La Mort de l’Auteur” (1968), in Œuvres complètes. T. III. 1968-1971, new edition revised, corrected and introduced by Éric Marty, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2002, p. 43.

iii Richard Prince, Why I go to the Movies Alone, New York, Tantam Press, pp. 69-70.

iv Rosalind Krauss,“Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (1979), in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and other ModernistMyths, 1986.

v Douglas Crimp, “Pictures”, in October, vol. 8, Spring 1979, pp. 75-88 ; the quotaton is taken from “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism”, in October, vol. 15, Winter 1980, p. 98.

articles liés

Le monde selon l’IA

par Warren Neidich

Paris noir

par Salomé Schlappi

Du blanc sur la carte

par Guillaume Gesvret