Ed Atkins

« Bastards », Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 6.06 – 7.09.2014.

« Ed Atkins », Kunsthalle Zurich, 15.02 – 11.05.2014.

Voir le film Godzilla dans une grande salle de cinéma ou le regarder en streaming un samedi soir, à moitié assoupie dans son lit, en trois fois, et avec une connexion Internet ralentie par la saturation du serveur, sont deux expériences fondamentalement étrangères l’une à l’autre. Je ne conseille par ailleurs à personne de regarder Gravity pendant un vol transatlantique : outre la nature angoissante de la comparaison qu’on ne manquera pas d’établir entre sa propre situation physique et celle du personnage de Sandra Bullock (des corps piégés dans un environnement artificiel en suspension dans un milieu hostile), l’écran est tout simplement trop petit et le son trop bas pour que le film fonctionne. Il s’agit peut-être d’une évidence mais il faut se souvenir parfois que la fréquentation d’un cinéma, quel que soit le type de film, d’ailleurs, et pas seulement les grosses productions, n’a rien à voir avec la consultation en ligne d’un fichier .mp4 ou .avi. Les conditions techniques de la réception varient considérablement, certes, mais, surtout, le corps se trouve engagé de manière tout à fait différente dans chacune de ces deux expériences.

De la même manière, si Youtube, Vimeo ou Vdrome sont des bénédictions pour les amateurs d’art, on sait aussi qu’ils ne se substituent pas à la situation qui est celle de l’exposition. Et cette évidence est particulièrement valable pour le travail d’Ed Atkins. Bien qu’il produise essentiellement de la vidéo et du texte, Atkins porte une attention particulière aux conditions spatiales d’exposition de son travail, comme son show à la Kunsthalle de Zurich l’a récemment démontré. La circulation des corps et la distribution du sens et des affects résultent d’un calcul d’une précision chirurgicale qui s’opère dès l’entrée de l’exposition. Imprimé sur papier et mis à l’échelle du mur, un texte accueille le spectateur. À la classique adresse « Dears, » succèdent trois pages d’une prose dense, traversée de marques d’oralité et pourtant d’une sophistication et d’un hermétisme très écrits, cette prose-même que l’artiste déploie dans chacune de ses œuvres. Ce texte, foncièrement opaque, ne fonctionne pas comme une œuvre à part entière (Atkins se refuse à considérer que ses textes ont une autonomie poétique), mais il crée un effet de seuil et pose un contexte de réception. Plus exactement, il esquisse à grands traits le système poétique de l’artiste. C’est un système contradictoire qui chasse le spectateur en même temps qu’il cherche à le séduire et à l’affecter, et qui se construit sur une approche résolument physique de l’art. Le texte, qui n’est pas intelligible au sens où il serait possible de le résumer en quelques mots, tourne par ailleurs autour d’une question centrale qui traverse tout son travail, cette revanche de la corporéité mise à mal par les technologies numériques de la représentation.

Vue de l’exposition / Installation view « Ed Atkins », Kunsthalle Zürich, 2014 © Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

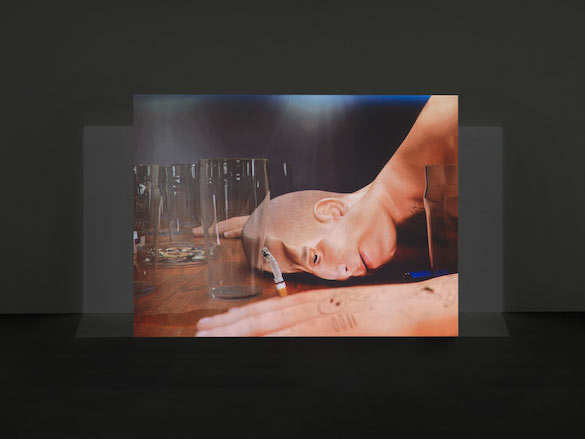

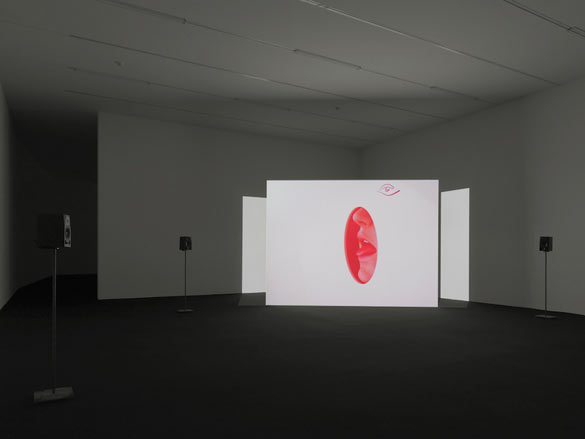

La première salle joue de manière assez classique le jeu de la rétrospective. Trois vidéos récentes sont visibles sur des écrans de taille moyenne, audibles au casque. Il s’agit d’Even Pricks, présentée pour la première fois à la Biennale de Lyon en 2013, de Warm, warm spring mouths (2013) et de Material Witness Or a liquid cop (2012). À l’opposé, des collages sur panneau de bois et d’acier reprennent certains motifs des vidéos. Loin d’être les pièces les plus intéressantes de l’exposition, ils ne livrent qu’une version appauvrie et commerciale du travail de l’artiste mais contribuent par leur présence à organiser l’espace autour d’une tension entre matérialité (la leur) et immatérialité (celle des trois vidéos). Autre effet de construction spatiale : un éclat sonore violent vient parasiter à intervalles réguliers l’écoute du son des vidéos au casque, créant un appel, un suspense physique qui oriente la déambulation vers la salle suivante. Les conditions matérielles de la réception changent radicalement dans cette seconde salle où est présenté Us Dead Talk Love, un diptyque vidéo (2012). Le corps est plongé dans le noir et entièrement saisi par l’image, avec deux grands écrans de la hauteur d’un corps posés à même le sol, mais aussi par le son en surround. La scénographie, comme à la Chisenhale Gallery de Londres où Us Dead Talk Love a été initialement présenté, n’est pas cinématographique : projetée de chaque côté des écrans, la lumière illumine le fond de la salle et crée une profondeur. Malgré la frontalité du dispositif de projection, on peut circuler autour de l’image et cette organisation dessine un véritable espace scénique. Tout le niveau supérieur de la Kunsthalle, enfin, est occupé par Ribbons (2014). Cette installation vidéo, inédite, se déploie sur trois salles que l’on traverse successivement. De larges écrans sont installés frontalement, créant dans chaque salle une situation cinématographique que vient complexifier la nécessaire déambulation.

Rien n’a été dit encore du contenu des œuvres elles-mêmes, de leurs motifs obsédants (le poil, la peau, les fluides, le bas corporel, le démembrement, les organes sexuels et non-sexuels, les cadavres, les virus, les allergies, l’abjection, bref, tout un tas de choses morbides gravitant autour du corps), des marqueurs de style et des effets omniprésents (HD, hyperréalisme, répétitions incessantes, cuts sonores violents, jeux d’inversion du fond et du premier plan, changement brutaux de filtres, de typographie), des registres récurrents (ironie, absurde, grotesque), ou de l’utilisation quasi maniaque des technologies numériques (animation, incrustation, montage du son, composition sonore, typographie…). Mais une description même abrupte et littérale de la scénographie de cette exposition démontre une chose : la manière dont Atkins envisage l’espace d’exposition constitue une porte d’entrée privilégiée dans son travail. Passant du texte aux images, le parcours de l’exposition est celui d’une forme de crescendo physique : il y a de plus en plus d’images, les installations sont de plus en plus larges, et la saisie du corps par les œuvres s’intensifie graduellement jusqu’à l’étage supérieur où elle devient totale. Atkins exploite ainsi tous les moyens à sa disposition pour saisir le public, de manière à la fois physique et affective : « Je crois que l’espace d’une galerie, un espace scénique ou un théâtre induisent une expérience, celle d’être près d’un autre corps et de ressentir ce corps [1] », expliquait-il récemment dans un entretien. Ceci ne signifie pas qu’il met en scène le triomphe de corps désirants (après tout, toutes ses œuvres sont hantées de cadavres et de corps malheureux) mais qu’une exposition, si elle peut être un événement mondain, institutionnel, commercial, est donc d’abord une situation physique : elle implique une présence du corps ici et maintenant.

Les technologies numériques ont été longtemps analysées sous le seul angle de la distribution, mais ce n’est pas ce qui intéresse Atkins, pas plus d’ailleurs que de nombreux artistes de sa génération. Pour autant, son travail ne s’inscrit pas dans les débats autour des concepts de New Aesthetic [2] ou du Post-Internet [3]. En un sens, c’est même tout le contraire. Atkins ne part pas, comme les artistes et critiques Maria Olson et Gene McHugh du constat d’une connectivité accrue, de l’intangibilité de l’information ou, comme le technologue et éditeur anglais James Bridle, de la contamination du réel physique par les technologies de l’information, aboutissant à un monde hybride et bizarre. Il se focalise justement sur la représentation d’une physicalité refoulée par tous ceux (les têtes de cons d’Even Pricks ?) qui clament à l’unisson que tout est en passe de devenir numérique ou immatériel. Par-delà la méfiance bien compréhensible pour les buzzwords que sont devenus « post-Internet » ou « New Aesthetic » dans la littérature artistique et même dans le marché de l’art [4], et le plaisir évident du trolling qu’il suscitent, il y a quelque chose de l’ordre de la misanthropie dans ce refus de partager l’enthousiasme générationnel pour le monde numérique, une misanthropie qui fait signe vers la vision du monde sombre et désespérée qu’Atkins déploie d’œuvre en œuvre.

Vue de l’exposition / Installation view « Ed Atkins », Kunsthalle Zürich, 2014 © Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

Ses réflexions sur la technologie HD donnent un aperçu assez juste de cette approche singulière, plus proche de Blanchot que de la prose de Wired, où les angoisses biographiques à propos de la mort, de la solitude, ou de la maladie se traduisent aussi sous la forme d’un discours sur la technologie. Dans Us Dead Talk Love, par exemple, l’utilisation d’un format vidéo mort, le 4:3, permet à l’artiste d’articuler la mélancolie des personnages et celle d’un état technologique. « Aujourd’hui, précise-t-il encore, une vidéo peut être tournée, montée, produite et montrée sans jamais prendre une forme physique (et si elle le faisait, quelle élégante et étrange forme pourrait-elle prendre?). L’aspect essentiellement immatériel de la HD va de pair avec sa promesse d’hyperréalité — de niveaux jusque-là inimaginables de netteté, de clarté, de crédibilité etc, transcendant le monde matériel pour révéler une espèce de perspective divine [5]». Utilisant le cadavre comme métaphore parodique de cette technologie de l’image, Atkins s’est donné pour tâche de créer un art matériellement embarrassant et qui puise dans le grotesque : « J’ai toujours souhaité que mon travail soit incisif et ce, le plus matériellement possible. Le seul matériau reconnaissable au cœur de toutes ces expériences numériquement modifiées, c’est notre corps. Le lieu de l’œuvre, en un sens, a toujours été le corps, le mien comme celui du spectateur. Il y a une tentative de parvenir à créer un affect de type corporel, à la fois de manière pauvre – via les technologies elles-mêmes – et d’une manière plus complexe, par le rythme et la cadence de l’œuvre dans sa manière de parler et de se donner à voir [6] ».

Ed Atkins Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths, 2013 Extrait du film HD avec son surround 5 .1 de 12’50 / Still from HD film with 5.1 surround sound 12’50. Courtesy Ed Atkins ; Cabinet, London

« Il s’est trouvé quelqu’un d’assez malhonnête pour dresser un jour, dans une notice d’anthologie, la table de quelques-unes des images que nous présente l’œuvre d’un des plus grands poètes vivants ; on y lisait : Lendemain de chenille en tenue de bal veut dire papillon. Mamelles de cristal veut dire : une carafe, etc. Non, monsieur, ne veut pas dire. Rentrez votre papillon dans votre carafe. Ce que Saint-Pol-Roux a voulu dire, soyez certain qu’il l’a dit. » Ces mots d’André Breton, tirés de l’Introduction au discours sur le peu de réalité (1924) nous invitent à ne pas essayer de traduire, comme le fit Remy de Gourmont directement visé ici par Breton qui se refuse cependant à le citer, les tropes récurrents du travail d’Atkins. Ils ne gagnent pas à être abordés sous l’angle de choses chiffrées qu’il faudrait décoder ; ils nous suggèrent surtout de nous pencher sur ce « peu de réalité » que génèrent les technologies digitales à l’aune d’une forme de surréalisme qui pourrait bien être relu, aujourd’hui, pour ce qu’il a eu à dire d’un certain état de distance avec la réalité physique. Mark Leckey, dont le travail sur les imaginaires des technologies de production du son et de l’image est devenu, en quelques années, une influence majeure pour toute une jeune génération d’artistes (et qui collabore avec la même galerie londonienne qu’Atkins, Cabinet), évoque d’ailleurs le texte de Breton dans son dernier livre The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, et spécialement ce projet de sculpture : réaliser des objets aperçus en rêve [7]. Et puisqu’il faut bien essayer de caractériser le travail complexe d’Ed Atkins, travail d’une densité dont on ne peut donner ici qu’un bref aperçu, forcément incomplet, on pourra simplement dire qu’il explore inlassablement le gouffre qui sépare, pour reprendre les termes de Nicholas Negroponte dans Being Digital, le monde des bits et celui des atomes, et noter que l’exposition de la Kunsthalle de Zurich et le catalogue qui l’accompagne constituent une très belle et bizarre introduction à ce gouffre. Plongez, maintenant.

- ↑ « Ed Atkins interviewed by Katie Guggenheim », septembre 2012

- ↑ Voir à ce sujet le premier post de J. Bridle sur la Nouvelle Esthétique, le 6 mai 2011. La transcription de sa conférence de 2012 « Waving at the machines ». Une mise au point récente sur le sens qu’il accorde à ce terme de « Nouvelle Esthétique », « The New Aesthetic and its Politics », 12 juin 2013 ou encore « An essay on the New Aesthetic », publié par l’auteur de science-fiction et futurologue américain Bruce Sterling dans Wired en 2012.

- ↑ Terme proposé par Maria Olson et Gene McHugh dans différents textes et entretiens à partir de 2008. Voir le livre de Gene McHugg, « Post-Internet », 2012 ; Artie Vierkant, « The Image Object Post-Internet » (2010) et Michael Connor, « What’s Postinternet Got to do with Net Art? », 1er Nov. 2013.

- ↑ Voir à ce propos l’excellent post de Brian Droitcourt et les torrents de commentaires qu’il a suscités, « Why I hate post-Internet art », Mars 2013.

- ↑ Ed Atkins, « Some Notes on High Definition, with apologies to M. Blanchot »

- ↑ « Interview with Beatrix Ruf », in Ed Atkins, Ed. Beatrix Ruf, Julia Stoschek et Thomas D. Trummer, JRP Ringier, Zurich, 2014, p. 114.

- ↑ Mark Leckey, The Universal Addressability of dumb things, Hayward Gallery Publishing, Londres, 2012, p. 5.

Ed Atkins

Seeing the film Godzilla in a large cinema or watching it streamed on a computer on Saturday evening, half dozing in bed, in three sessions, and on a heavily overloaded Internet connection, are two very dissimilar experiences. I don’t advise anyone to watch Gravity during a transatlantic flight: apart from the harrowing comparison you are bound to make between your own physical situation and that of the character played by Sandra Bullock (bodies trapped in an artificial environment suspended in hostile surroundings), the screen is simply too small and the sound too low for the film to work. It might seem obvious but we need to remind ourselves from time to time that a visit to a cinema for whatever type of film, and not just big-budget movies, is completely different to watching an .mp4 or .avi film online. Of course the technical environment in which you experience the film varies considerably, but, above all, the body (of the viewer) is engaged in a very different manner for each.

Similarly, even though YouTube, Vimeo and Vdrome are godsends for art lovers, we know that they don’t take the place of a real exhibition. And this is particularly true for the work of Ed Atkins. Although he produces mainly video and text, he sets great store by the spatial layout of his works, as his recent show at Kunsthalle Zurich demonstrated. The physical circulation of the bodies and the organization of the sense and affects are the result of a surgically precise calculation that takes effect the moment you walk in. Printed on paper and blown up to cover the whole wall, a text welcomes the visitors. The traditional address of “Dears” is followed by three pages of dense prose characterized by indications of orality, yet also by a very carefully scripted sophistication and obscurity, the same prose that Atkins uses in his works. Deliberately enigmatic, this text does not function as a work in its own right (Atkins refuses to consider that his texts are endowed with a poetic autonomy), but it gives the impression of a threshold and a receptive context. To be more specific, it offers a broad brush representation of the artist’s poetic system. Paradoxically, this system deters visitors while also attempting to charm and move them, and is based on a resolutely physical approach to art. The text, which remains unintelligible in the sense that it cannot be summarized in just a few words, revolves around an issue central to all his work: the riposte of the corporeality made to suffer at the hands of digital technologies.

Vue de l’exposition / Installation view « Ed Atkins », Kunsthalle Zürich, 2014 © Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

In classic manner, the first room functions as a retrospective. Three recent videos can be viewed on medium-sized screens and listened to through headphones. The titles of these videos are Even Pricks, first presented at the Biennale de Lyon in 2013, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), and Material Witness OR A Liquid Cop (2012). Facing them, collages on panels of wood and steel echo some of the motifs seen in the videos. Far from being the most interesting pieces in the exhibition, they only offer a diluted and commercial version of Atkins’ work but their presence helps organize the space around the dimension of materiality (theirs) and immateriality (that of the three videos). Another characteristic of the spatial construction is that the videos’ soundtrack heard on the headphones is disturbed at regular intervals by a powerful burst of sound that creates an exhortation, a physical suspense, to the viewer to head for the next room. The material circumstances in the second room are changed radically for the presentation of Us Dead Talk Love, a video diptych (2012). The body is immersed in darkness and completely absorbed by the two giant screens, the height of a body, standing on the ground, and subsumed by the surround sound. As at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, where Us Dead Talk Love was first presented, the setting is not cinematographic: a light projected from either side of the screens illuminates the back of the room, creating depth. Despite the frontality of the projection device, it is possible to move around the image, which creates a very scenic space. The entire first floor of the Kunsthalle is occupied by Ribbons (2014). This new video installation is distributed through three rooms, which are visited in succession. Large screens are installed frontally, turning each room into a sort of cinema auditorium, which complicates the necessary perambulation.

Nothing has yet been said about the contents of these works, their obsessive motifs (hair, skin, fluids, the lower part of the body, dismemberment, sexual and non-sexual organs, cadavers, viruses, allergies, abjection, in short, a series of gruesome themes revolving around the body), style markers, and the omnipresent effects (HD, hyperrealism, incessant repetitions, violent sound cuts, inversions of the background and foreground, abrupt changes of filter and typography), recurrent registers (irony, absurdity, the grotesque), and the almost maniacal use of digital technologies (animation, incrustation, sound editing, sound composition, typography, etc.). But even a short and literal description of the setting of this exhibition points up something particular: the way in which Atkins lays out the exhibition space offers a unique key for entering into his work. After passing from text to images, the exhibition takes on a form of physical crescendo, with an increasing number of images, more and more imposing installations, and the absorption of the body by the works gradually intensifies until it becomes total on the top floor. Atkins exploits all the means at his disposal to capture the public physically and affectively: “I think that a gallery space, performance space or theatre introduces the reality of being near another body and feeling that body”, he recently explained in an interview [1]. This does not mean that he presents the triumph of desiring bodies (after all, all his works are haunted by cadavers and wretched bodies) but that an exhibition – if it is a social, institutional and commercial event – is fundamentally a physical situation: it implies a bodily presence here and now.

Ed Atkins Vue de l’exposition / Installation view, « Us Dead Talk Love », Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2012. Courtesy Ed Atkins ; Cabinet, London. Photo : Andy Keate

Digital technologies have long been considered simply from the perspective of distribution but that is not what interests Atkins, at least no more than it does many artists of his generation. For all that, his work does not fall into the discussion surrounding the concepts of New Aesthetic [2] or Post-Internet [3]. In one sense, it’s the exact opposite. Unlike the artists and critics Maria Olson and Gene McHugh, Atkins does not start from the fact of greater connectivity, the intangibility of information, or, like the English technologist and publisher James Bridle, the contamination of physical reality by information technologies, resulting in a hybrid, bizarre world. Rather, Atkins focuses on the representation of a physicality repressed by all those (the heads of the fools in Even Pricks?) who cry in unison that everything is in the process on the way to becoming digital or immaterial. Beyond the very understandable mistrust of the buzzwords “post-Internet” and “New Aesthetic [4], and the trolling pleasure they give, there is something almost misanthropic in this refusal to take part in the generational enthusiasm for the digital world, a misanthropy that echoes the sombre, desperate world that Atkins unfolds before us in work after work.

His thoughts on HD technology offer an accurate glimpse of this unusual approach, one that is closer to Blanchot than to Wired, in which his personal anxieties regarding death, solitude and disease also take the form of a discourse on technology. In Us Dead Talk Love, for example, the use of an obsolete video format (4:3) allows him to express the sadness of the characters and a technological state. “Today” he explains, “a video can be shot, edited, produced and displayed without ever once resolving into a physical form. (And if it did, what sleek alien shape might it take?) The essentially immaterial aspect of HD is concomitant to its promise of hyperreality – of previously unimaginable levels of sharpness, lucidity, believability, etc., transcending the material world to present some sort of divine insight. [5]” Using the cadaver as a parodical metaphor of this defunct image technology, Atkins has devoted himself to creating a materially cumbersome art which draws on the grotesque: “Something I’ve always wanted my work to do is to be incisive, in a conspicuous material manner. And pretty much the only recognisable material in so many digitally inflected experiences is our body. The work’s site, in a way, has always been bodies, mine and the viewer’s. There’s an attempt to achieve a corporeal kind of affect, both somewhat cheaply – via the technologies themselves – and in a more complicated way through the rhythms and meters of the work’s way of speaking and showing itself [6]”.

Vue de l’exposition / Installation view « Ed Atkins », Kunsthalle Zürich, 2014 © Stefan Altenburger Photography Zurich

“A rather dishonest person one day, in a note contained in an anthology, made a list of some of the images presented to us in the work of one of our greatest living poets. It read: ‘The next day the caterpillar dressed for the ball’…meaning ‘butterfly’. ‘Breast of crystal…meaning carafe’. Etc, No, indeed, sir. It means nothing of the kind. Put your butterfly back in your carafe. You may be sure Saint-Pol-Roux said exactly what he meant.” These words written by André Breton in his Introduction to the Discourse on the Paucity of Reality (1924) invite us not to try and translate – as did Remy de Gourmont, who was directly targeted here by Breton despite the author’s refusal to cite him – the recurring tropes in Atkins’ work. They do not gain by being considered items of code that require deciphering. Above all, they suggest that we should ponder that “paucity of reality” that digital technologies generate as a form of surrealism; indeed, surrealism itself might well be revisited today in view of what it had to say on a certain distance from physical reality. Mark Leckey, whose work on the imaginaries at work in sound and image production technologies has become, in just a few years, a major influence on a whole generation of young artists (he also works with Atkins’ London gallery, Cabinet), evokes Breton’s text in his most recent book, The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, and especially the sculptural project of creating objects that appear in dreams [7]. And as an attempt must be made to describe the complex work of Ed Atkins, an oeuvre so multifaceted that only a brief and necessarily incomplete glimpse can be made here, we can simply say that he tirelessly explores the gulf that separates the worlds of bits and atoms, to use Nicholas Negroponte’s words in Being Digital, and to note that the exhibition at the Zurich Kunsthalle and its catalogue provide a very beautiful and bizarre introduction to that gulf. Make the jump now.

- ↑ « Atkins interviewed by Katie Guggenheim », Chisenhale Gallery, September 2012

- ↑ On this, see the first post in James Bridle’s blog, 6 May 2011. The transcription of his 2012 lecture « Waving at the machines ». His latest tweak to the acceptation he gives to the term New Aesthetic, in « The New Aesthetic and its Politics », 12 june 2013 and « An essay on the New Aesthetic », published by the American science-fiction author and futurologist Bruce Sterling in Wired in 2012.

- ↑ A term proposed by Maria Olson and Gene McHugh in different writings and interviews as from 2008. See Gene McHugh’s book Post-Internet (2012); Artie Vierkant, « The Image Object Post-Internet » (2010) and Michael Connor, « What’s Postinternet Got to do with Net Art? », 1 Nov. 2013.

- ↑ On this, see Brian Droitcourt’s excellent post and the torrents of comments it stimulated, « Why I hate post-Internet art », March 2013.

- ↑ Ed Atkins, « Some Notes on High Definition, with apologies to M. Blanchot »

- ↑ “Interview with Beatrix Ruf”, in B. Ruf, J. Stoschek and T. Trummer (eds.) Ed Atkins (Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2014), p. 114.

- ↑ Mark Leckey, The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things (London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2012), p. 5.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Nicolas Roggy, Mélanie Gilligan, Marc Leckey resident,

articles liés

Biennale Son

par Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

par Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

par Sarah Matia Pasqualetti