Facile, difficile, l’art de Stephen Felton

“I’m not trying to be cool

I only wanna be kind”.

Real Estate, Wonder Years.1

Brut. Cru. Pur. Écru. Âpre. Sensible. Novice. Inexpérimenté. Ignorant. Très froid. Froid et humide. Peindre à main levée demande une certaine décontraction, alliée à une concentration intense. Il faut être à la fois sûr de son geste et relativement tolérant quant au résultat. En clair, il faut déjà l’avoir expérimenté. Cette technique, Stephen Felton la tient sans doute de Dan Walsh, dont il a été l’assistant. Mais sa peinture a quelque chose d’encore plus nonchalant, plus direct. Pendant des siècles, la peinture a été avant tout une histoire de savoir-faire. Puis Duchamp ou Rodtchenko ont élevé l’incompétence au rang d’œuvre d’art. Felton déclare croire avant tout en l’acte de peindre. De quoi s’agit-il ? Il y a une multitude de choses peintes, de gens ou de machines qui peignent, en dehors du champ de l’art. À la bombe, au pinceau, avec des pochoirs. Sur les murs, au sol, sur les matériaux de chantiers ou les arbres qu’on va couper. Tous les objets industriels (voitures, meubles, jouets) sont également peints, avec des techniques nettement plus efficaces que celles des artistes. L’acte de peindre est donc répandu et universel ; il sert à marquer, à signifier. Il peut aussi être gratuit : peindre, c’est quelque chose qu’on fait, que tout le monde a déjà fait. Mais tout le monde ne devient pas pour autant artiste. Dans l’imaginaire collectif, l’artiste peintre est celui qui a d’abord un talent et qui acquiert ensuite naturellement une technique hors-norme, un peu à la manière d’un sportif de haut niveau. Cette idée d’une peinture de haut niveau est encore très présente dans l’abstraction de la deuxième moitié du vingtième siècle, notamment dans l’expressionnisme abstrait : une peinture doit avoir de la prestance, elle doit élever l’esprit du spectateur, l’impressionner, le bouleverser. La personnalité exceptionnelle de l’artiste remplace en quelque sorte son savoir-faire, elle en est la preuve. Dans sa manière d’aborder les choses, Stephen Felton se place délibérément à distance de cette vision idéalisée de l’artiste. Il peint comme n’importe qui le ferait, sans technique particulière. Avec un pinceau trempé dans un pot de peinture, à la recherche d’une spontanéité difficile.

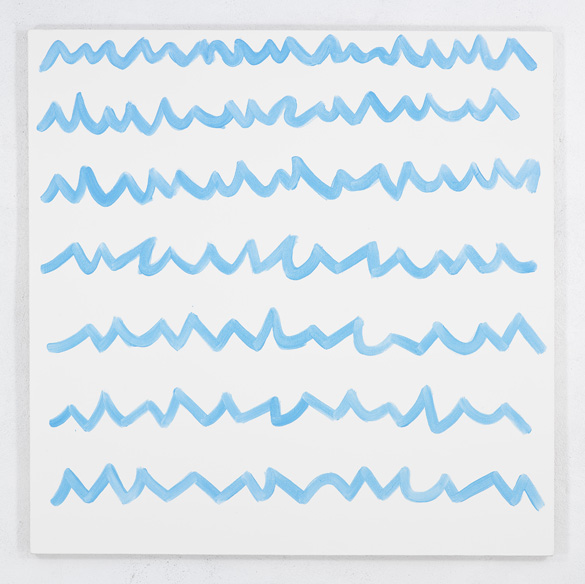

Ses peintures, on les reconnaît pourtant facilement. Souvent, ce sont des tableaux d’assez grand format, des toiles partiellement enduites, peintes de lignes d’une ou deux couleurs formant des pictogrammes semi-abstraits. Certains motifs reviennent régulièrement : arcs-en-ciel ou lignes circulaires parallèles, lignes en dents de scie (comme celles des graphiques ou du cours de la bourse, mais qui pourraient tout aussi bien être des vagues ou des montagnes), formes de bulles de BD éclatées (celles qu’on utilise pour les exclamations ou les bruits), flèches dirigées vers le haut (celles qu’on trouve sur les caisses, les cartons d’emballage et les tableaux de Martin Barré). Lignes, cercles, points forment un vocabulaire simple, récurrent, quasi naïf. Il ne s’agit pas vraiment de primitivisme mais plutôt d’une interprétation personnelle de l’idée du réductionnisme historique. Les tableaux de Felton sont quelquefois posés directement à même le sol. Parfois, ils sont retournés contre le mur et peints au dos. Dans ce cas, la peinture peut contourner le châssis (c’est-à-dire l’éviter mais aussi en souligner les contours) ou au contraire être appliquée indifféremment sur l’envers de la toile et sur le châssis. Ailleurs, un carton peint est fixé sur une toile monochrome, du scotch noir compose une grille incertaine. Tous ces choix relèvent d’un pragmatisme antidogmatique évident. L’acte de peindre est un acte simple, spontané, abordable. Mais cette facilité est aussi difficile car elle doit s’accorder avec une attitude délibérée. Il faut un certain courage pour abandonner ce qu’on sait de l’art et de son histoire, de ses maîtres et de leur intimidante maîtrise. Il faut aussi surmonter l’injonction de productivité, accepter que le travail soit aussi une absence de travail, une recherche faite d’échecs et d’insatisfactions.

Full Spectrum, 2011. Acrylique sur toile et carton / acrylic on canvas and carboard,167,6 x 167,6 cm. Photo : Jeffrey Sturges

Stephen Felton explique qu’il fait un tableau sur l’instant : il tend la toile, l’enduit rapidement et peint ce qui lui vient (c’est assez surprenant mais Barnett Newman procédait aussi de cette manière). S’il estime que ce n’est pas réussi, il dégrafe la toile aussitôt. Une peinture doit donc sa réussite à quelque chose de mystérieux, qui va à l’opposé des conceptions dogmatiques de l’abstraction minimale. Historiquement, les artistes minimalistes puis conceptuels ont eu raison de rejeter l’existentialisme de l’expressionnisme abstrait, même si cette vision de l’art reste quelque peu honorable quand elle est vécue jusqu’au bout. Mais ils ont eu tort de penser qu’en dissociant l’art de la vie, ils élimineraient du même coup toute référence au monde et à la personnalité. Au contraire, pour paraphraser Newman, ils ont fait le monde à leur image. Aujourd’hui, nous ne pouvons plus naïvement utiliser le langage de ces artistes car c’est le langage du monde lui-même : celui du design et de l’architecture minimale, du happening publicitaire, du concept marketing. L’art abstrait ne sera pas impersonnel parce qu’on aura méthodiquement gommé toute trace de subjectivité dans son œuvre, mais parce qu’on aura fait de son œuvre une pratique en accord avec sa vie, qui est la vie que tout le monde vit. Aller à l’atelier, ouvrir un pot de peinture, tendre une toile, la peindre, nettoyer ses pinceaux, rentrer chez soi, faire sa vaisselle, lire ses mails, voir des amis, de la famille : toutes ces choses sont à mettre sur le même plan. L’art de Stephen Felton nous rappelle que la peinture peut aussi se vivre, être à proprement parler une « pratique », comme on dit pratiquer un art martial, le skate ou une religion.

1 Wonder Years, extrait de l’album Days de Real Estate sorti en 2011.

“I’m not trying to be cool

I only wanna be kind”.

Real Estate, Wonder Years.1

Rough. Crude. Pure. Raw. Harsh. Novice. Inexperienced. Ignorant. Very cold. Cold and dank. Painting freehand calls for a certain relaxation, combined with intense concentration. You have to be both sure of your stroke and relatively tolerant of the outcome. Put plainly, you have to have already tried your hand at it. Stephen Felton probably gets this technique from Dan Walsh, whose assistant he has been. But his painting has something even more nonchalant and more direct about it. For centuries painting was above all a story of know-how. Then Duchamp and Rodchenko promoted incompetence to the rank of artwork. Felton says that he believes above all in the act of painting. What does this involve? There is a whole host of painted things, and of people and machines who paint, outside the field of art. Using spray cans, brushes, and stencils. On walls, on the ground, on the materials of building sites, and on trees about to be felled. All industrial objects (vehicles, furniture, toys) are also painted, with techniques that are decidedly more effective than those used by artists. So the act of painting is widespread and worldwide; it serves to mark and signify. It may also be gratuitous: painting is something you do, that everyone has already done. But not everyone becomes an artist. In the collective imagination, the painter is a person who, first and foremost, has a talent, and who subsequently naturally acquires an exceptional technique, a bit like a top-flight athlete. This idea of top-flight painting was still very present in abstraction in the latter half of the 20th century, in particular in Abstract Expressionism: a painting must have a certain bearing, it must raise the viewers spirits, impress them, and (deeply) move them. In a way, the artist’s exceptional personality replaces his expertise, it is proof thereof. In the manner in which Stephen Felton broaches things, he intentionally removes himself from this idealized vision of the artist. He paints the way any old Tom, Dick or Harry might do, without any specific technique. With a brush dipped into a pot of paint, looking for a spontaneity not easy to come by.

Yet his paintings are easily recognizable. They are often quite large pictures, canvases partly covered, painted with lines in one or two colours forming semi-abstract pictograms. Some motifs regularly recur: rainbows and parallel circular lines, serrated lines (like those used for graphs or stock exchange rates, but which could just as well be waves or mountains), forms of exploded comic strip bubbles (the ones used for exclamations and noises), upward arrows (the ones you find on crates, boxes and Martin Barré pictures). Lines, circles and dots make up a simple, recurrent, almost naïve vocabulary. What is involved is not really primitivism, but rather a personal interpretation of the ideas of historical reductionism. Felton’s pictures are sometimes set directly on the ground. At times they are turned round against the wall and painted on the back. In this case, the paint may go round the stretcher (meaning that it avoids it, but also underscores the outlines) or, on the contrary, it may be applied willy-nilly on the other side of the canvas and on the stretcher. In other instances, a piece of cardboard is glued onto a monochrome canvas, and black scotch tape forms a vague grid. All these choices stem from an obvious anti-dogmatic pragmatism. The act of painting is a simple, spontaneous, accessible act. But this easiness is also difficult, because it must go hand-in-hand with a deliberate attitude. It takes a certain courage to abandon what you know about art and its history, its masters and their intimidating mastery. It is also important to overcome the dictates of productivity, and accept that the work is also an absence of work, a quest made up of failures and moments of dissatisfaction.

Stephen Felton explains how he makes a picture on the spot: he stretches the canvas, quickly coats it, and paints what comes to mind (surprising though it may be, Barnett Newman also went about things like this). If Felton reckons that it has not worked, he immediately unstaples the canvas. So a painting owes its success to something mysterious, that runs counter to the dogmatic conceptions of minimal abstraction. Historically, the Minimalist and then the Conceptual artists were quite right to reject the existentialism of Abstract Expressionism, even if that vision of art remains not very honourable when it is taken to the limit. But they were wrong to think that by dissociating art from life, they would by the same token do away with any reference to the world and to personality. On the contrary, to paraphrase Newman, they made the world in their image. Nowadays, we can no longer naively use the language of those artists, because it is the language of the world itself: that of design and minimal architecture, of the publicity happening, and the marketing concept. Abstract art is not impersonal because all trace of subjectivity in its work has been methodically done away with, but because its work has been made into a praxis that is in harmony with its life, which is the life that everyone lives. Going to the studio, opening a pot of paint, stretching a canvas, painting it, cleaning your brushes, going back home, doing the dishes, reading your e-mails, seeing friends and family: all these things are to be put on the same level. Stephen Felton’s art reminds us that painting can also be lived; it can, properly speaking, be a practice, the way we refer to practicing a martial art, skating, or a religion.

1 Wonder Years, an excerpt from Real Estate’s album Days, released in 2011.

articles liés

Biennale Son

par Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

par Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

par Sarah Matia Pasqualetti