Hamish Fulton

« En marchant », Crac Sète, 30.10.2013 – 02.02.2014.

« Comme agir et travailler, marcher exige un engagement corps et âme dans le monde, c’est une façon de connaître le monde à partir du corps, et le corps à partir du monde. [1] »

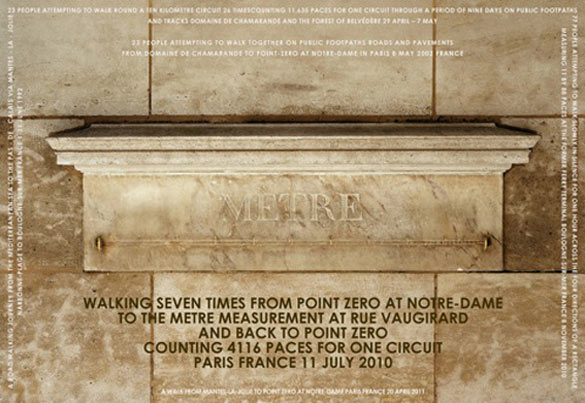

Cela fait une dizaine d’années que l’artiste anglais n’avait foulé les chemins ni les trottoirs français si l’on excepte les moments notables que furent la marche entre le domaine de Chamarande et Paris en 2003 et celle réalisée à l’occasion de la biennale de Belleville, en 2010, pour laquelle l’arpenteur impénitent avait relié sept fois en une journée le point zéro au mètre étalon [2] en un parcours aussi symbolique que mémorable. Invité par le centre régional d’Art contemporain de Sète à réaliser une exposition personnelle, l’artiste d’outre-Manche trouve là l’occasion de réaliser une de ses impressionnantes pérégrinations en reliant l’Atlantique à la Méditerranée et de traverser les Pyrénées d’ouest en est en empruntant pour partie les sentiers de grande randonnée mais aussi en inventant de nouveaux itinéraires, marque de fabrique d’un artiste qui revendique la déambulation à travers les espaces naturels et urbains comme une certaine forme de liberté. Les grandes salles du CRAC de Sète, avec leurs volumes hors normes et la minéralité de leur architecture, ne sont pas pour rien dans ce retour en France : elles lui permettent de restituer de la manière la plus fidèle cette expérience de la traversée du paysage qui figure au premier rang de ses motivations.

Hamish FULTON, Mètre, 2012 Édition en couleur (15 ex.), Papier Canson Baryta 310 g, 153 x 105 cm Courtesy Bernard Chauveau Éditeur / Le Néant Éditeur.

La longue marche

Hamish Fulton appartient à une tradition artistique, celle de la marche, de la performance, du happening, qui agrège de nombreuses préoccupations allant du désir de dématérialisation de l’œuvre d’art commun aux artistes conceptuels et à ceux du Land Art, à la volonté de reconsidérer l’importance du corps à l’intérieur de l’expérience esthétique ; sa pratique croise aussi celle d’autres marcheurs célèbres dont les mobiles furent purement protestataires, comme Martin Luther King qui emprunta à la grande figure de la révolution indienne Gandhi cette manière de manifester ses idéaux politiques qui allie non-violence et déambulation. La marche — qui, par-delà son caractère anodin, est, paradoxalement, pour de nombreux savants, à l’origine de notre singulière destinée humaine — a la faculté, comme toutes les choses simples en apparence, de soulever des questionnements fondamentaux lorsqu’elle se voit incorporée dans le champ de l’art. Dans son ouvrage désormais classique, Marcher, Créer, Thierry Davila fait remonter les prémices de cet art du nomadisme aux premières tentatives de Rodin pour faire de la sculpture un anti-monument, ne plus lui assigner de localisation et la faire entrer de plain-pied dans le modernisme en lui conférant un caractère autoréférentiel [3]. Mais comme le dit Davila un peu plus loin, le « nomadisme moderniste » ne suffit plus désormais à caractériser une pratique contemporaine qui ne s’embarrasse guère de ce genre de restrictions [4]. Il est cependant assez tentant de replacer Fulton dans cette lignée en lui réattribuant les critères retenus par Rosalind Krauss pour caractériser la condition négative du modernisme :

« une perte de site, un nomadisme, un état de déracinement absolu… [5] »

En effet, l’Anglais considère sa production artistique comme une sculpture se déplaçant à l’intérieur du paysage, il ne cherche pas à lui assigner de lieu spécifique et déclare ne pas vouloir produire d’objets autres que ceux nécessaires à la restitution stylisée de l’expérience vécue [6]. Bien que Fulton semble vouloir se démarquer des artistes du Land Art en l’affirmant à même ses wallpaintings [7], il est indéniable qu’il partage le même renoncement envers l’œuvre d’art réifiée, le même attrait pour les espaces « naturels » débarrassés tant que faire se peut de toute présence humaine et une certaine méfiance à l’égard de la grande ville même s’il lui arrive cependant d’y faire des marches comme ce fut le cas justement pour la « performance » bellevilloise.

Restituer / resituer

Une restitution « classique » ne sied pas vraiment à la pratique de Fulton : on ne peut guère imaginer qu’il se satisfasse d’un compte-rendu de son expérience qui prenne la forme d’un banal objet d’art, préoccupation qu’il partage avec son ami Richard Long : « pour Fulton, le corps est uniquement un instrument perceptif tandis que, pour Long, c’est également un instrument de dessin [8] », nous dit Francesco Careri, comparant les difficultés éprouvées par les deux artistes anglais dans la transmission de ce qui relève en priorité de l’expérience, avec le sentiment que pour Fulton la tâche est encore plus ardue et ne peut être de toutes manières qu’un succédané, « le problème de la représentation du parcours est résolu par le moyen d’images et de textes graphiques qui témoignent de l’expérience de la marche, avec cette conscience de ne jamais pouvoir y parvenir par la représentation [9] ». Pour transmettre cette expérience de la marche, Fulton utilise principalement deux médiums, celui de la peinture et celui de la photo. Mais pas n’importe quelle peinture, pas n’importe quelle photo. La peinture de Fulton est d’essence minimale sans renoncer pour autant à la complexité, elle accepte des formes géométriques, des symboles, de l’écriture et même une légère dose de figuration. Toutefois, même quand ce dernier s’en prend à la représentation des montagnes, il ne s’agit pas pour autant de faire dans la fantaisie : ses formes sont épurées, stylisées à l’extrême. Il s’agit, pour ses grandes peintures de paysage, de peindre de larges aplats franchement délimités qui conservent la même valeur chromatique. On n’est pas loin de l’univers d’un Olivier Mosset, à la différence près que la peinture du Suisse ne représente… que la peinture. En ce qui concerne ses grandes peintures murales « à slogan », on pense immédiatement à Lawrence Weiner : de larges énoncés qui barrent la surface, la même typographie qu’on retrouve d’un mural à l’autre. Pour autant, la comparaison s’arrête à un examen plus précis de la forme et du contenu : chez Weiner, les mots « sont » les peintures, ils envahissent les surfaces, débordent du mur, s’échappent en tous sens, quand chez Fulton les inscriptions obéissent à une discipline stricte, les mots étant choisis en fonction de leur nombre de lettres qui forment des grilles régulières et ne sortent jamais du cadre. Cependant, le rapprochement avec l’artiste américain ne paraît pas complètement déplacé, lui qui est capable de prononcer une sentence que l’Anglais pourrait reprendre à son compte :

« Pour moi, l’art est un “réaménagement” du monde. Lorsque je me lève chaque matin je me considère comme un artiste opérationnel. Je ne me dis pas que le monde est en train de disparaître. Je ne cours pas après le monde non plus. Je fais simplement partie du courant de vie qui me porte. [10] »

Hamish FULTON, The way, 1996 (Japon). Lettrage vinyle sur peinture / Vinyl lettering over wallpainting, 557,5 × 543 cm. Courtesy Hamish Fulton; galerie Torri, Paris.

Concernant la photographie, Fulton fait preuve de la même exigence de précision qu’il met en œuvre dans sa peinture : ses photos sont très strictement cadrées et font toujours état de la même rigueur d’exécution. Chaque cliché doit témoigner de la plénitude que l’on est censé ressentir face au paysage. La « cinéplastique [11] » à l’œuvre chez Fulton n’a rien à voir avec celle de ces artistes arpenteurs de la mégalopole, les Orozco, Alÿs et autres Stalker, il est même patent que la marche fultonnienne s’éloigne en tous points de la tendance dominante à investir les situations urbaines. Sa pratique puise ses origines dans les années soixante et soixante-dix et porte les stigmates d’une nature encore idéalisée ; il ne semble absolument pas en phase avec le rythme saccadé de la ville, ses ruptures, ses blancs, ses accélérations qui fondent l’amour que les situationnistes portent à la ville, lieu de la dérive, dont la seule traduction possible ne peut se trouver que dans le montage cinématographique ; à preuve, la marche qu’il réalise entre le point zéro et le mètre étalon en 2010 est la répétition sept fois du même trajet entre ces deux pôles, symboles d’une abstraction enfouie, pour le moins désuète à l’heure du GPS. Tout témoigne chez l’artiste de la recherche d’une sérénité intérieure, d’un calme et d’une quiétude qu’il ne saurait trouver dans les à-coups de la grande ville mais bien dans le refuge des cimes des Pyrénées ou de l’Himalaya, aussi il semble assez naturel que l’expérience fultonnienne du monde s’incarne dans les médiums de la recherche d’un temps stabilisé, ceux de la peinture et de la photographie.

This is not land art

Hamish Fulton a toujours cherché à se démarquer du Land Art auquel de nombreux critiques ont voulu l’associer. Il est vrai qu’il est tentant d’y incorporer l’artiste anglais et certaines publications ne s’en sont pas privées : l’ouvrage de chez Taschen qui regroupe l’essentiel des « land artistes » lui accorde quatre pleines pages et le considère comme un représentant à part entière de ce mouvement qui a fortement influencé l’art de la fin du XXe siècle [12]. En effet, bien des thèmes favoris de ces artistes du paysage [13] se retrouvent chez Fulton, comme par exemple le refus de la marchandisation de l’art : aux yeux de la plupart de ces artistes, Smithson en premier, ce qui importe c’est l’expérience de l’art, et cette dernière ne peut être transmise via un objet accroché au mur d’une galerie, d’où l’idée de mettre à distance cette confrontation esthétique pour forcer le regardeur à faire l’effort d’aller à la rencontre de l’œuvre. Ce dernier devra se contenter de ce contact éphémère avec l’œuvre qui ne supporte pas de substitut (c’est aussi pour cela que la stratégie idéaliste de ces artistes faillira, victime de la pression des galeries qui n’y trouvent pas leur compte). On retrouve ici l’une des préoccupations majeures de Fulton, la quasi intransmissibilité de l’expérience esthétique, sauf que chez Fulton elle prend la forme du refus de la production d’objets « médiateurs » alors que, chez les artistes du Land Art, elle se traduit par l’obligation d’aller sur site faire l’expérience de l’œuvre. Un autre rapprochement possible avec ces derniers est son attrait certain pour les espaces « vierges » des déserts de l’Ouest américain. Si Fulton refuse ce qu’il considère comme des atteintes majeures à l’intégrité de la nature (et il est vrai que des œuvres comme celles de Heizer ou de Smithson n’ont rien à envier à de grands chantiers de travaux publics), cherchant seulement à se déplacer à l’intérieur du paysage comme une espèce de sculpture vivante, il semble évident qu’il ressent fortement cette attirance pour les paysages désertiques et leur symbolique multiple qu’il ira plutôt chercher, lui, du côté des montagnes de l’Himalaya. Nous évoquions précédemment Richard Long, lui aussi régulièrement répertorié au sein du Land Art, et souvent associé à Hamish Fulton avec qui il partage cet amour de la marche et ce souhait de ne pas s’attaquer à « l’environnement » : ses inscriptions dans le paysage restent le plus souvent délicates et s’opposent à la production spectaculaire des artistes américains. À la différence de Fulton toutefois, il est plus souple avec l’usage des objets rapportés dont la collecte au cours de ses déambulations constitue la base de ses sculptures à venir, autant de traces destinées à la « reconstitution » des sites traversés. Par ailleurs, la production d’une documentation photographique nécessaire à la restitution le rapproche formellement de Fulton même s’il se situe plus dans une dimension conceptuelle.

Hamish FULTON, Footpath, 2012 (Pyrénées) Photographie et texte (pièce encadrée), 76 x 94 x 3 cm Courtesy de l’artiste et TORRI, Paris.

Néo-pèlerin ?

Sous les allures de la simplicité, l’œuvre de Fulton se révèle bien plus complexe qu’elle n’en a l’air, croisant l’héritage de l’art minimal et conceptuel dont elle est issue, le chemin du Land Art dont elle partage certains aboutissants, le traitement formel de la peinture monochrome dont elle apprécie l’épure et enfin le Protest Art qui lui permet de participer du devenir du monde. C’est ce dernier aspect qui retiendra ici notre attention puisqu’il condense les nombreuses orientations sensibles, philosophiques mais aussi politiques de l’artiste. Il est tentant de faire remonter cette pratique aux figures évoquées plus haut, celle du Mahatma Gandhi et de Martin Luther King dont les marches protestataires et pacifistes à travers leur pays respectif signèrent la singularité de leur action et marquèrent d’autant plus les esprits. Une personnalité beaucoup moins connue que ces géants fut celle de Peace Pilgrim qui, au début des années cinquante aux États-Unis, se mit à parcourir à pied des distances fantastiques à travers tout le continent [14]. Relevant incontestablement de la tradition chrétienne du pèlerinage dont elle emprunte à ses débuts les attributs habituels de piété, de frugalité et de dépouillement, les marches de Peace Pilgrim acquièrent progressivement une dimension profane en se rapprochant des thèmes développés par les pacifistes américains et notamment les opposants à la guerre de Corée. Ainsi, lors de ses traversées transcontinentales qui pouvaient durer plusieurs années, elle arborait à même ses vêtements des slogans clairement destinés à marquer l’attention de ses contemporains comme « quinze mille kilomètres à pied pour le désarmement » ou « du Pacifique à l’Atlantique à pied pour la paix ». Ce dernier est particulièrement frappant dans son énonciation et rappelle la manière qu’a Fulton d’associer ses marches à une « cause » politique volontairement négligée suite à l’embarras qu’elle est susceptible de provoquer à l’égard d’une nation qu’on préfère ménager : le grand wallpainting Chinese economy présenté à Sète fait clairement état d’une dimension critique à l’encontre de la situation tibétaine que menace la grande puissance voisine de ses volontés hégémoniques. La série de ces pièces tibétaines exprime la quintessence d’un art plutôt « méditatif » qui ne s’empêche cependant pas de se mêler de sordides enjeux terrestres… Peut-être est-il nécessaire de remonter encore plus loin, aux antiques articulations entre marche et philosophie de l’école péripatéticienne, en passant par Les rêveries du promeneur solitaire de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, pour expliquer la capacité de cet art de la marche à convoquer une telle complexité sous l’apparence d’une si grande simplicité ; ou bien encore de se replonger dans les débats qui continuent d’agiter les anthropologues et autres paléontologues cherchant à démontrer que le passage à la bipédie fut la cause majeure de l’accession des premiers humains à la faculté de penser [15], pour inscrire la démarche de Fulton dans cette grande chaîne des « marcheurs-penseurs ». Toujours est-il que l’artiste anglais déclare produire l’essentiel de ses pensées artistiques au cours de ses longues marches…

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, L’art de marcher, (2000), 2002 pour la traduction française, Arles, Actes Sud, Babel, p. 46.

- ↑ Le point zéro est situé à une cinquantaine de mètres devant l’entrée de Notre-Dame, sur l’Île de la Cité, dans le 4e arrondissement de Paris. La borne routière qui matérialise ce point dans les pavés du parvis de la cathédrale prend la forme d’une rose des vents gravée au centre d’un médaillon octogonal en bronze entouré d’une dalle circulaire en pierre divisée en quatre quartiers, chacun d’eux portant l’une des inscriptions suivantes en lettres capitales : « point », « zéro », « des routes », « de France ». Quant au mètre étalon, sa troisième concrétisation légale est toujours conservée au pavillon de Breteuil à Sèvres.

- ↑ Thierry Davila, Marcher, créer, 2002, Paris, Éditions du Regard, p. 19.

- ↑ Id., p. 21.

- ↑ Rosalind Krauss dans L’Originalité de l’avant-garde et autres mythes [1985], 1993, trad. Jean-Pierre Criqui, Paris, Macula, p. 115, citée par Thierry Davila, op.cit., p. 21.

- ↑ Propos recueillis lors du vernissage au CRAC de Sète le 30 octobre 2013.

- ↑ This is not Land Art, Alaska, Mai-Juin 2004.

- ↑ Francesco Careri, Walkscapes, la marche comme pratique esthétique, Nîmes, Jacqueline Chambon, 2013, p. 153.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Extrait d’un entretien entre Lawrence Weiner et Jack Wendler, in Nathalie Guiot, Artistes et collectionneurs, Blackjack éditions, 2013, p. 112.

- ↑ Terme inventé par Élie Faure pour renforcer le sens du mot plastique jugé insuffisant pour décrire l’art nomade et repris par Thierry Davila, op.cit., p. 21.

- ↑ Land Art, Taschen, 2007.

- ↑ Land Art est une abréviation de Landscape Art (art paysager), le terme fut utilisé en premier par Gerry Schum en 1969.

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, L’art de marcher, p. 80 et sq.

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, op. cit., chapitre III, « L’élévation et la chute, Théories sur la bipédie », p. 48 et sq.

Hamish Fulton

« Like doing things and working, walking calls for a body-and-soul involvement in the world, it’s a way of getting to know the world through the body, and the body through the world. [1] »

For the past ten years or so this British artist has not trodden the roads and pavements of France, with the exception of those notable moments represented by the walk between the Domaine de Chamarande and Paris in 2003, and the one made for the Belleville Biennale in 2010, for which the unrepentant walker connected the zero point to the standard metre [2] seven times in one day, on a route that was as symbolic as it was memorable. Invited by the Regional Contemporary Art Centre [CRAC] in Sète to hold a solo show, the artist from across the Channel duly found an opportunity to make one of his impressive peregrinations by linking the Atlantic to the Mediterranean and crossing the Pyrenees from west to east, partly using main hiking trails but also inventing new itineraries, trademark of an artist who reckons that walking through natural and urban spaces represents a certain form of freedom. The large rooms of the CRAC in Sète, with their non-standard volumes and the minerality of their architecture, are not for nothing in this return to France: they enable him to re-create in the most faithful way this experience of walking through the landscape which is at the forefront of what motivates him.

The long march

Hamish Fulton belongs to an artistic tradition—walking, performance, and happenings—which encompasses numerous issues, ranging from the desire to de-materialize the work of art which is shared by conceptual artists and artists involved with Land art, to the desire to reconsider the body’s importance within the aesthetic experience; his praxis also overlaps with that of other famous walkers and marchers, whose motives were purely to do with protest, like Martin Luther King who borrowed that manner of displaying his political ideals, which combines non-violence and walking, from the great figure of the Indian revolution, Mahatma Gandhi. Marches and walks—which, over and above their harmless nature, lie, paradoxically, for many scholars, at the root of our particular human destiny—have the ability, like all seemingly simple things, to raise fundamental questions when incorporated in the field of art. In his now classic book, Marcher, Créer, Thierry Davila takes the premises of this art of nomadism back to Rodin’s first attempts to turn sculpture into an anti-monument, no longing assigning it a location and introducing it straight into modernism by endowing it with a self-referential character [3]. But as Davila puts it a little later, “modernist nomadism” is now longer enough to hallmark a contemporary practice which is hardly bothered by this kind of restriction [4]. It is nevertheless quite tempting to resituate Fulton in this tradition by re-attributing to him the criteria used by Rosalind Krauss to describe the negative condition of modernism:

« …a loss of site, a nomadism, an absolute state of uprootedness… [5] »

Hamish FULTON, Brain Heart Lungs, 2000 (Tibet). Lettrage vinyle sur peinture / Vinyl lettering over wallpainting, 689 × 543 cm. Courtesy Hamish Fulton; galerie Torri, Paris.

The Englishman actually regards his artistic output like a sculpture moving within the landscape, he does not seek to assign it a specific place and declares that he does not want to produce objects other than those necessary for the stylized re-creation of the experience lived [6]. Although Fulton seems to want to be different from artists involved in Land Art, by asserting as much through his wallpaintings [7], it is undeniable that he shares the same renunciation of the reified work of art, the same attraction to “natural” spaces relieved as much as is possible of all human presence and a certain distrust with regard to the big city even if he sometimes does do walks in them, as was the case, precisely, for the Belleville “performance”.

Re-creating/Re-situating

“Classic” re-creation is not really part of Fulton’s praxis: it is hard to imagine that he would be satisfied with a report of his experience that takes the form of a common-or-garden art object, a concern he shares with his friend Richard Long: “For Fulton, the body is solely a perceptive instrument, whereas, for Long, it is also a drawing instrument” [8], Francesco Careri tells us, comparing the difficulties experienced by both English artists in the transmission of what stems, in priority, from experience, with the feeling that, for Fulton, the task is still more arduous and can only, in any event, be a substitute, “the problem of the representation of the route is solved by means of images and graphic texts which illustrate the experience of the walk, with that consciousness of never being able to achieve it through representation [9].” To get this experience of the walk across, Fulton uses mainly two media, painting and photography. But not any old painting, and not any old photograph. Fulton’s painting is essentially minimal, but does not turn its back on complexity, it accepts geometric forms, symbols, writing and even a slight dose of figuration. However, even when this latter grapples with the representation of mountains, this still does not involve fantasy—the forms are spare and extremely stylized. For his large landscape paintings, it is a matter of painting large and clearly delimited flat tint areas which keep the same chromatic value. We are not far from the world of an artist like Olivier Mosset, with the slight difference that the Swiss artist’s painting only represents… painting. As far as Fulton’s large wall paintings “with slogans” are concerned, Lawrence Weiner immediately springs to mind: large declarations running across the surface, and the same typography that recurs from one mural to the next. But the comparison stops on a closer examination of the style and content: with Weiner, the words “are” the paintings, they invade the surfaces, they spill away from the wall, they escape in every sense, while with Fulton the inscriptions comply with a strict discipline, the words being chosen on the basis of the number of letters which form regular grids and never go beyond the frame. But comparison with the American artist does not seem totally out of place, capable as he is of uttering a sentence which the Englishman might use on his own behalf:

“To me, art is about reorganizing the world. When I get up in the morning, I consider myself a working artist. I don’t tell myself that the world is disappearing, nor do I run after it. I’m simply part of the flow of life that carries me with it. [10] ”

Where photography is concerned, Fulton shows the same requirement of precision which he applies in his painting: his photos are very strictly framed and always show the same rigour of execution. Each photo must illustrate the fullness we are meant to feel in front of the landscape. The “cinéplastique” [11] at work with Fulton has nothing to do with that of those artists who criss-cross megalopolises, like Orozco, Alÿs and Stalker, it is even patently clear that the Fultonian walk is in every way removed from the predominant tendency to use urban situations. His praxis finds its origins in the 1960s and 1970s and bears the marks of a still idealized nature; he seems totally out of sync with the jarring pace of the city, its breaks, its blanks, its accelerations which underpin the Situationists’ love of the city, place of drifting, whose only possible translation is to be found in cinematographic montage; proof being that the walk he made between the zero point and the standard metre in 2010 was the repetition seven times of the same route between these two poles, symbols of a buried abstraction, at the very least obsolete in the age of the GPS. Everything, with this artist, attests to the quest for an inner serenity, a tranquillity and a peace-and-quiet that he could not find in the jolts and judders of the big city, but rather in the refuge of the peaks of the Pyrenees and the Himalaya, so it seems quite natural that the Fultonian experience of the world is incarnated in the media involved in the search for a stabilized time— painting and photography.

Hamish FULTON, The Second Full Moon of May, 1998 (Japan). 704 × 558 cm. Photo : Richard Sprang, © Crac LR 2013.

This is not Land Art

Hamish Fulton has always tried to set himself apart from the Land Art with which many critics have wanted to associate him. It is true that it is tempting to include the English artist in the movement, and one or two publications have done just that: the book published by Taschen which includes all the main “land artists” devotes four full pages to him and regards him as a fully-fledged representative of this movement which had a powerful influence on art at the end of the 20th century [12]. The fact is that many of the favourite themes of these artists [13] are to be found in Fulton’s work, like, for example, the refusal of art’s commercialization and commodification: in the eyes of most of these artists, Smithson first among them, what matters is the experience of art, and this cannot be transmitted via an object affixed to a gallery wall, whence the idea of putting this aesthetic confrontation at a remove to force the beholder to make the effort to go towards the work, and encounter it. The viewer will have to be content with this ephemeral contact with the work which does not put up with any substitute (it is also for this reason that the idealistic strategy of these artists would fail, victim of the pressure of galleries not finding enough profit there. Here we find one of Fulton’s major preoccupations, the virtual impossibility of transmitting the aesthetic experience, except that with Fulton it takes the form of the refusal to produce “go-between” objects, while, among artists involved with Land Art, it is translated by the obligation to go to the site to enjoy the experience of the work. Another possible comparison with these latter is his attraction to the “virgin” spaces of the deserts in the American West. If Fulton rejects what he regards as major assaults on the integrity of nature (and it is true that works such as those of Heizer and Smithson are every bit a match in this respect for the damage done by large public works projects), trying just to move about within the landscape like a sort of living sculpture, it seems clear that he strongly feels this attraction to desertscapes and their multiple symbolism which he, for his part, seeks out in the mountains of the Himalaya. We earlier mentioned Richard Long, who is also regularly listed in the Land Art directory and is often associated with Hamish Fulton, with whom he shares this love of walking and this wish not to attack the “environment”: his inscriptions in the landscape usually remain subtle and contrast with the spectacular output of the American artists, but unlike Fulton, he is more flexible with the use of objects brought back, the collection of which during his walks forms the basis of his sculptures in the offing, so many traces destined for the “reconstruction” of the sites passed through. What is more, the production of a photographic documentation necessary for the re-creation draws him formally close to Fulton, even if he is more in a conceptual dimension.

Hamish FULTON, Counting 49 Barefoot Paces, 2010 (Planet Earth) – Photographie Richard SPRANG © CRAC LR 2013.

Neo-pilgrim?

In the guise of simplicity, Fulton’s work turns out to be far more complex than it looks, mixing the legacy of Minimal and Conceptual Art from which it stems, the Land Art track, with which it shares certain outcomes, the formal treatment of monochrome painting whose sparseness it appreciates, and Protest Art which enables it to take part in the world’s future development. It is this latter aspect that we shall focus on here, because it condenses the artist’s numerous perceptible orientations, philosophical and political alike. It is tempting to trace this praxis back to the figures mentioned earlier, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, whose pacifist protest marches through their respective lands marked the unusualness of their actions, and influenced minds even more. A personality much less well-known than those giants was that of the Peace Pilgrim who, in the early 1950s in the United States, started to cover fantastic distances on foot throughout the continent [14]. Stemming indisputably from the Christian tradition of pilgrimage, and from the outset borrowing its usual attributes of piety, frugality and spare simplicity, the Peace Pilgrim marches gradually acquired a lay dimension by drawing closer to the themes developed by American pacifists and opponents of the Korean war. So during their transcontinental traverses, which could last for several years, this figure displayed on his actual clothing slogans that were clearly intended to catch the attention of his contemporaries, such as “Walking 10,000 Miles for World Disarmament” and “Walking Coast to Coast for Peace”. This latter calls to mind the way Fulton has of associating his walks with a deliberately neglected political “cause”, following the embarrassment that it is capable of causing with regard to a nation that people prefer to treat tactfully : the large wallpainting Chinese Economy on view in Sète clearly records a critical dimension with regard to the Tibetan situation under threat from the mighty neighbouring power with its hegemonic desires. The series of these Tibetan pieces expresses the quintessence of a rather “meditative” art which does not, however, stop it from becoming mixed up with sordid terrestrial challenges… Perhaps it is necessary to go still further back, to the ancient links between walking and the philosophy of the Peripatetic School, by way of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, to explain the capacity of this art of walking to summon such complexity in the guise of such great simplicity; or plunge once more into the debates which are still exercising anthropologists and palaeontologists trying to demonstrate that the passage to bipedalism was the major cause of the first human beings’ access to the faculty of thought [15], in order to include Fulton’s approach in that great line of “walker-thinkers”. The fact still remains that the English artist says that he produces the essence of his artistic thoughts during his long walks…

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, 2000, Viking Penguin.

- ↑ The zero point—i.e. the ‘centre of Paris’ from which all distances in the country are measured—is situated about 50 yards from the entrance to Notre Dame, on the Île de la Cité, in the 4th arrondissement in Paris. The marker which forms this point in the cobbles of the cathedral’s forecourt takes the shape of a wind rose engraved at the centre of an octagonal bronze medallion surrounded by a circular stone slab divided into four quarters, each one of them bearing one of the following inscriptions in capital letters: “POINT”, “ZERO”, “DES ROUTES”, “DE FRANCE”. As far as the standard metre is concerned, its third legal model is still held in the Pavillon de Breteuil at Sèvres.

- ↑ Thierry Davila, Marcher, créer, 2002, Paris, Éditions du Regard, p. 19.

- ↑ Id., p. 21.

- ↑ Rosalind Krauss in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths [1985], 1996, MIT Press, quoted par Thierry Davila, op.cit., p. 21.

- ↑ From an interview at the opening at the CRAC in Sète on 30 October 2013.

- ↑ This is not Land Art, Alaska, May-June 2004.

- ↑ Francesco Careri, Walkscapes, la marche comme pratique esthétique, Nîmes, Jacqueline Chambon, 2013, p. 153.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Excerpt from an interview between Lawrence Weiner and Jack Wendler, in Nathalie Guiot, Artistes et collectionneurs, Blackjack editions, 2013, p. 121.

- ↑ A term invented by Élie Faure to heighten the meaning of the word plastique deemed inadequate for describing nomadic art, and borrowed by Thierry Davila, op.cit., p. 21.

- ↑ Land Art, Taschen, 2007.

- ↑ Land Art is an abbreviation of Landscape Art; the term was first used by Gerry Schum in 1969.

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, op. cit.

- ↑ Rebecca Solnit, op. cit., chapter III, “ Rising and Falling: The Theorists of Bipedalism”.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Iván Argote, Tohé Commaret, Jack Warne, Yan Tomaszewski, Alun Williams,

articles liés

Biennale Son

par Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

par Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

par Sarah Matia Pasqualetti