Jonathan Binet

Le plus haut possible. De dos / de face. La petite moitié. Les œuvres de Jonathan Binet ont parfois des titres, mais pas toujours. Il semble plus judicieux de dire les œuvres que les peintures — bien qu’il soit ici essentiellement question de peinture — car il serait plus adéquat de parler de la peinture de Jonathan Binet plutôt que des peintures de Jonathan Binet. Bien sûr, les œuvres existent, indépendantes les unes des autres, catégorisées, si ce n’est sous des titres, au moins par des chiffres de dimensions et de dates. Mais c’est lors de l’accrochage, lorsqu’elles s’additionnent — selon le terme choisi par l’artiste pour ce processus — que ces œuvres créent ce fameux tout supérieur à l’ensemble de ses parties, que sa peinture prend réellement corps. Il s’agit alors d’inverser le temps, de « réinventer les causes», de réinjecter l’accidentel, l’imprévu, dans le cours de l’exposition que l’on suppose généralement le fruit d’une longue suite de décisions a priori. Dans sa forme finale ou, en tout cas, dans sa forme accrochée, l’œuvre vient confirmer ce que le hasard a pu suggérer.

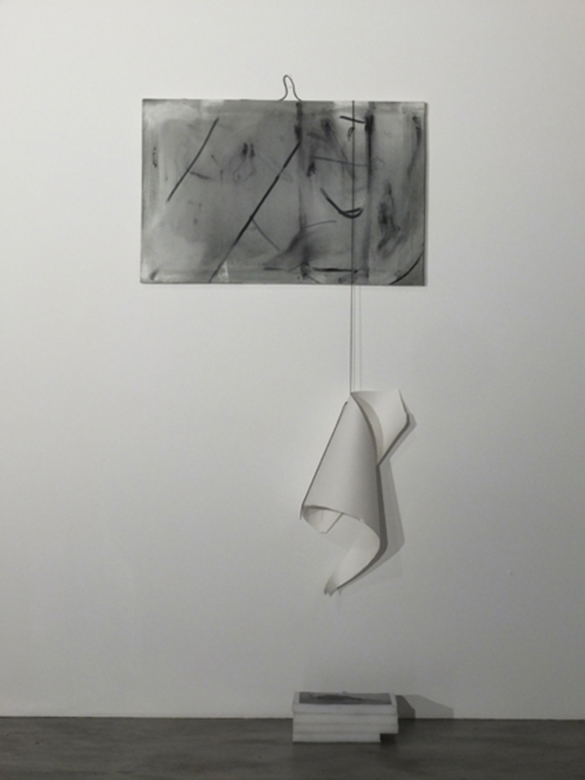

Vue de l'exposition/exhibition view, la petite moitié, 2012. Capc Bordeaux, photo Blaise Mercier. Courtesy galerie Gaudel de Stampa.

La petite moitié peut être aussi celle de l’acte de peindre, entamé par l’artiste et terminé par la toile elle-même en un ultime retrait du peintre supprimant encore un degré de médiation entre la main et la toile. Jonathan Binet perpétue, à l’instar d’un Martin Barré ou d’un Jackson Pollock, par exemple, une certaine réduction du faire pictural à la tension corporelle entre le peint et le peintre, réduction paradoxale puisqu’elle laisse la part belle à l’outil rendu ici maître ou presque de la situation. Lorsque la bombe de peinture qui a suivi les mouvements de l’artiste se retrouve coincée entre la toile et le châssis, elle n’a d’autre choix que de s’épancher contre la toile qu’elle traverse alors de coulures noires. Et c’est à la fois le souffle retenu du pinceau de calligraphie chinoise et l’énergie pulsionnelle de l’Action Painting qui s’y révèlent.

De dos / de face : la peinture passe indifférement d’un versant à l’autre de la toile, jouant avec elle comme d’un pochoir, d’une contre-forme pour atteindre le mur ; réminiscence peut-être d’un geste pictural primitif, celui du pigment soufflé sur les contours de la main. De cette forme d’autoportrait en creux, Jonathan Binet fait ressortir une dimension temporelle assez flagrante tant dans la durée d’exécution que l’on peut suivre par le tracé linéaire sprayé presque d’un seul tenant que par la couleur qui change à chaque intervention.

Vue de l'exposition/exhibition view, la petite moitié, 2012. Capc Bordeaux, photo Blaise Mercier. Courtesy galerie Gaudel de Stampa.

Parfaitement à son aise dans les 650m2 sinueux que lui dédie le CAPC, la peinture de Jonathan Binet scande l’espace et s’amalgame des objets qui viennent la ponctuer comme pour en rappeler la corporalité, peut-être chorégraphique : une chaussette, un lacet… L’espace est travaillé à taille humaine, la hauteur d’accrochage est définie par la hauteur d’exécution de la peinture. Les intervalles entre les tableaux importent presque autant que les toiles elles-mêmes, investis de gestes simples comme un coup de spray rapide sur une vis laissée là ou une ficelle tendue tout du long du parcours de l’exposition. La peinture est parfois plus présente sur la toile non tendue qui déborde du châssis que sur le carré blanc qui lui est théoriquement dévolu.

Le plus haut possible, quant à lui, résulte tout simplement de la tentative d’aller déposer de la peinture le plus haut possible.

Jonathan Binet

Le plus haut possible. De dos/de face. La petite moitié – As High as Possible. Back/Front. The Small Half. Jonathan Binet’s works sometimes have titles, but not always. It seems a little more shrewd to call them works rather than paintings—although here painting is what is essentially involved—because it would be more suitable to talk of Jonathan Binet’s painting rather than his paintings. Needless to say, the works exist, independently of one another, pigeonholed, if not by titles, then at least by the ciphers of dimensions and dates. But it is during the hanging, when the works start to add up—to use the word chosen by the artist for this process—that they create the all too famous whole-greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts, and Binet’s painting really takes shape. So it is a matter of reversing time, “re-inventing causes”, re-injecting something accidental, the unforeseen, in the throes of the exhibition which we usually presuppose to be the outcome of a lengthy series of preconceived decisions. In its final form or, in any event, in its hung form, the work confirms what chance has only managed to suggest.

Vue de l'exposition/exhibition view, la petite moitié, 2012. Capc Bordeaux, photo Blaise Mercier. Courtesy galerie Gaudel de Stampa.

The Small Half may thus be the act of painting, embarked on by the artist and completed by the canvas itself in a final withdrawal by the artist, getting rid of another degree of mediation between hand and canvas. Like artists such as Martin Barré and Jackson Pollock, for example, Jonathan Binet perpetuates a certain reduction of the pictorial act to the physical tension between the painted and the painter, a paradoxical reduction because it gives pride of place to the tool here made master, or almost, of the situation. When the paint spray which has followed the artist’s movements is caught between the canvas and the stretcher, it has no other choice but to spread itself against the canvas which it then traverses in black runoffs. And it is at once the held breath of the Chinese calligraphic brush and the vibrational energy of Action Painting that are here revealed.

Back/Front: the paint moves willy-nilly from one side of the canvas to the other, playing with it like a stencil, a counter-form to reach the wall; a recollection, perhaps, of a primitive pictorial gesture, that of pigment blown over the outlines of the hand. From this form of self-portrait in the negative, Jonathan Binet brings out a time-based dimension which is quite flagrant both in the period of execution that can be followed by the sprayed linear lines—sprayed almost in one fell swoop—and by the colour which shifts with each reworking of the picture…

Vue de l'exposition/exhibition view, la petite moitié, 2012. Capc Bordeaux, photo Blaise Mercier. Courtesy galerie Gaudel de Stampa.

Jonathan Binet’s painting, which is thoroughly at ease in the tortuous 650 sq.m/7,000 sq.ft allotted him by the CAPC, paces the space and connects with the objects which punctuate it, as if like a reminder of the painting’s choreographic physicality: a sock, a shoe lace… The space is worked at a human scale, the height of the hanging is defined by the painting’s height of execution. The gaps between the pictures matter almost as much as the canvases themselves, filled with simple gestures like a quick spray of paint on a screw left there or a piece of string running throughout the exhibition circuit. The paint is sometimes more present on the unstretched canvas outside the stretcher than on the white square which is theoretically assigned to it.

As High as Possible, for its part, is quite simply the result of an attempt to apply paint as high as possible.

Jonathan Binet, The Small Half, CAPC, Bordeaux, from 15 November 2012 to 10 February 2013.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Kate Crawford | Trevor Paglen, Thomas Bellinck, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Giorgio Griffa, Hedwig Houben,

articles liés

Biennale Son

par Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

par Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

par Sarah Matia Pasqualetti