Walter Benjamin : Histoires des œuvres

Tenter d’identifier une origine est sûrement malvenu ici. Mais, puisqu’il faut commencer par quelque part, prenons comme point de départ ce qui apparaît comme un début. Il est en effet possible que l’histoire qui nous intéresse débute en 1986 à Belgrade et Ljubljana où se tiennent respectivement « Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10 » et l’« International Exhibition of Modern Art ». La première, organisée par Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935) présente ses fameuses toiles suprématistes, exposées exactement de la même façon que sur le célèbre cliché qui documente cette exposition tenue en 1915-16 à Saint-Pétersbourg. La deuxième est une copie de l’Armory Show, dont elle reprend le sous-titre, exposition qui introduit l’art moderne aux États-Unis en 1913.

Kazimir Malevich The Last Futurist Exhibition, 1985-86. Appartement privé / Private appartment, Belgrade.

Ces deux projets, bien que relevant historiquement d’enjeux et de contextes différents, présentent, en cette année 1986, quelques points communs. Leurs titres, les œuvres exposées et leurs modes de présentation sont proches de celles qu’elles copient. Néanmoins, les réalisations qui y sont présentées ne masquent pas leur nature de répliques. Grossièrement réalisées, elles ressemblent sommairement aux œuvres originales sans toutefois en être des imitations fidèles. D’après les photographies et les textes qui documentent ces événements, il semble que les objets présentés soient bien plus des signes renvoyant à des œuvres connues, formant ainsi des rappels d’événements passés importés dans le présent et ayant subi quelques altérations dues à ces déplacements dans le temps.

Cette même année voit une autre résurrection, celle de Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) qui propose à Ljubljana une conférence intitulée Mondrian ’63–’96. L’acteur qui endosse le rôle du philosophe présente un exposé portant sur un corpus de peintures de Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) datées de 1963 à 1996. Après s’être interrogé sur la nature de ces réalisations, il affirme qu’il est impossible de connaître l’auteur de ces copies mais que leur datation et leur facture, qui ne passeraient aucun test d’authenticité, indiquent qu’il ne peut s’agir du travail d’un faussaire. Walter Benjamin en conclut que, probablement, ces peintures ont vocation à apparaître dans la collection d’un musée. Elles seraient alors présentées dans la période qui leur correspond, les années quatre-vingt. Si tel était le cas, un spectateur suivant la chronologie proposée en ce lieu serait face à un phénomène étrange, un bégaiement de l’histoire remettant en cause les fondements sur lesquels elle s’écrit. Mais surtout il devrait en conclure qu’il a là affaire à deux productions similaires pourtant née d’intentions tout à fait différentes, soit deux mêmes peintures aux conceptions distinctes.

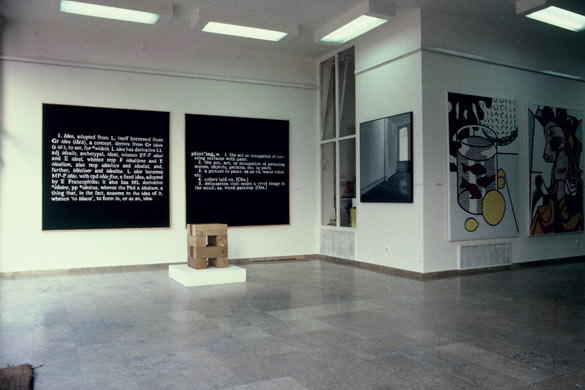

International Exhibition of Modern Art, New York, 1996, Gallery of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, 1986.

Outre leurs datations sans lien avec l’histoire de l’art que nous connaissons, ces trois projets ont en commun de présenter des répliques dans des cadres caractéristiques de la production de l’écriture de l’histoire de l’art du XXe siècle. Les expositions et les études des historiens sont en effet les jalons qui soulignent l’apparition de tel ou tel paradigme, de telle ou telle école, de tel ou tel courant de pensée et, surtout, fondent les chapitres d’une histoire commune. Le déroulement de celle-ci s’appuie sur la recherche de gestes créateurs qui renouvellent le genre et proposent de nouvelles façon de faire. Bref, c’est une histoire qui considère qu’une nouvelle étape est franchie à chaque fois qu’un positionnement original et inédit est identifié.

Or, les projets qui nous intéressent ici proposent, à l’inverse, des copies. De par leur apparence, qui ne camoufle pas leur statut, et leur datation, sans lien avec celle des originaux, les productions montrées dans ces projets n’ont pas vocation à se substituer à celles qu’elles imitent.

Pour tenter d’en sonder les objectifs, nous pouvons invoquer ici l’analyse que fait Nathalie Leleu des répliques qui hantent certains musées [1]. Dans ce texte, l’auteure se penche sur plusieurs reconstitutions d’œuvres disparues ou inaccessibles commanditées par des conservateurs de musées. Les personnes responsables des copies de Victory Boogie-Woogie (1943-1944) de Mondrian, reproduite en 1946 au Stedelijk Museum, du Cabinet des Abstraits (1927-1928) de El Lissitzky, reconstitué en 1968 au Provinzialmuseum de Hanovre, ou du Modèle du Monument à la IIIe Internationale (1919-1920) de Vladimir Tatline, refait en 1979 au Centre Pompidou, ne sont pas des faussaires eux non plus. Ils se nomment respectivement Willem Sandberg, Alexander Dorner et Pontus Hultén. Ils sont guidés par une seule vocation, celle de travailler leur médium de prédilection : l’exposition. Pour produire la narration sur laquelle s’appuie leur pratique ils ont besoin d’objets à présenter et si l’original n’est pas disponible une copie peut jouer son rôle.

Comme l’explique Leleu, « si les copies et les reconstitutions assument la même fonction symbolique que les œuvres “authentiques” qu’elles côtoient dans l’espace d’exposition du musée moderne, leur introduction au sein de la collection – via l’inventaire, procédure normative et validante – signale une rupture dans le régime conventionnel de l’œuvre d’art, en même temps qu’un changement de paradigme historique dont ces objets sont les symptômes marginaux mais déclarés » [2]. Autrement dit, dans leur désir de réunir des ensembles signifiants, les responsables de l’écriture de l’histoire de l’art par sa monstration ouvrent la boîte de Pandore. Celle de la copie. Celle qui nie la suprématie du geste original.

Leleu rappelle par ailleurs que Walter Benjamin, dans les premières lignes de L’œuvre d’art à l’ère de sa reproductibilité technique, signale que « la réplique d’artiste, la copie et la reconstitution ont toujours agi comme des auxiliaires de la création artistique, dotés de fonctions précises qui varient selon les époques » [3]. La fonction que recouvrent les reconstitutions précitées est strictement pédagogique, elle est liée aux nécessités de l’exposition. C’est-à-dire qu’elles ont moins vocation à porter le nom de leurs auteurs (Piet Mondrian, El Lissitzky ou Vladimir Tatline) qu’à agir à titre d’exemples pour illustrer le propos des conservateurs qui les commanditent. Orphelines, ces réalisations ne sont pas à appréhender pour y déceler un geste créateur original mais apparaissent comme des objets « ouverts et dévolus au discours et aux enjeux de la mémoire, au-delà de leur substance » [4]. Ainsi ce n’est plus l’artiste et son ouvrage que l’on admire dans ce type de production mais l’histoire qui les sacre chef-d’œuvres.

Les Fleurs Américaines Une exposition conçue par / curated by Élodie Royer et Yoann Gourmel en collaboration avec / with le Salon de Fleurus, New York et le Museum of American Art, Berlin / Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau. Photo : Martin Argyroglo. Autobiographie d’Alice B. Toklas, collection du Salon de Fleurus, New York.

C’est peut-être guidé par une réflexion similaire sur la différence entre une œuvre envisagée comme un objet portant la trace de son créateur et son statut d’icône historique que, dans l’« International Exhibition of Modern Art », la facture des objets est à contre-sens de leur typologie de production « authentique ». Incluant les œuvres de certains artistes nés après 1913, y sont présentées, entre autres, Définition de Joseph Kosuth réalisée à la peinture à l’huile et datée de 1905 et Fontaine de Marcel Duchamp sous la forme d’une sculpture en plâtre visiblement faite à la main.

De façon moins démonstrative, toutes les peintures que l’on peut voir dans les trois expositions qui composent « Les fleurs américaines » au Plateau sont réalisées avec soin mais présentent une facture bien éloignée de celles copiées. De fait, par leur nature explicite de substitut, elles rejouent notre relation à l’art et à son histoire depuis l’invention de la reproduction, depuis qu’il est possible de voir les œuvres sans nous déplacer jusqu’à elles mais en les faisant venir à nous. Dans les projections de diapositives et de PowerPoint des cours d’histoire de l’art ou dans les manuels ne sont montrés que des remplaçants, des doublures qui ont les caractéristiques nécessaires à la démonstration qui motive leur apparition mais pas toutes celles de l’œuvre étudiée.

C’est cette histoire de l’exemplarité qui parcourt « Les fleurs américaines » où sont exposées des reproductions d’articles de journaux, de photographies documentant telle ou telle présentation d’œuvres, présentées sous la même forme que les peintures. Ici, l’histoire de la présentation, par l’exposition, l’historicisation ou le journalisme, est présentée au même niveau que le geste original de l’artiste qui disparaît un peu plus au profit d’une mise en narration. Une mise en narration largement soulignée par la succession des trois projets réunis sous le titre « Les fleurs américaines ». Elle s’écrit dans la succession de trois personnages. La première est Gertrude Stein et son Salon de Fleurus, ouvert à Paris entre 1903 et 1913, que l’on peut considérer comme la première réunion d’œuvres modernes, et pour cela comme la première pierre à l’édifice de l’historicisation de l’art moderne. Le second est Alfred H. Barr, premier directeur d’un musée dédié à l’art moderne, le Museum of Modern Art ouvert en 1929, où se sont écrites les première lignes d’une histoire et d’une classification typologique de la modernité européenne. La troisième est Dorothy Miller qui, avec des expositions comme « 14 Americans » en 1946 ou « Abstract Art in America » en 1951, prolongea cette narration pour y intégrer l’expressionnisme abstrait alors naissant et ainsi sanctifié comme prolongement logique de cette histoire.

Les œuvres deviennent ainsi des documents au service de la rationalisation historique. Le geste de copie et de reconstitution qui parcourt « Les fleurs américaines » ne fait que le souligner, autant qu’il montre la façon dont ces documents ont été utilisés pour écrire une histoire. De fait, parées de ce nouveau statut, les œuvres n’ont plus comme auteur celui qui les a produites mais celui qui les montre, celui qui parle à travers elles.

On est alors en droit de demander qui est la personne qui produit de tels projets qui, sous le nom générique de Museum of American Art, se présente comme un « établissement pédagogique » [5]. Un projet pédagogique qui, contrairement à ceux des conservateurs, ne tente pas d’écrire une histoire mais de décrire la construction de celle-ci. Là encore c’est un fantôme qui apparaît. De la même façon que le narrateur se cache dans la manipulation d’œuvres, celui qui en dévoile le fonctionnement se cache dans l’anonymat et parle en réanimant des personnages disparus. Celui qui revient le plus souvent est Walter Benjamin, souvent présenté comme le porte-parole du Museum of American Art.

Dans un entretien, il explique qu’il ne croit plus en l’art. Selon lui « l’art existe uniquement dans “la narration (story) de l’art”, principalement dans l’histoire (history) de l’art et les musées. Et [qu’il] ne croit pas que ce soit une histoire objective et universelle, mais la simple invention d’un certain type de société » [6]. Or, cette invention se fonde sur le respect de codes et de paramètres qui valident son écriture. Au sujet de la façon dont cette histoire s’écrit, Walter Benjamin rappelle que pour certaines personnes croyant en l’histoire chrétienne, une peinture représentant une Madone à l’enfant a pour personnages principaux ces deux individus. La même peinture présentée dans un musée qui, lui, croit en l’histoire de l’art, aura pour personnage principal le peintre qui l’a réalisée. Walter Benjamin en conclut que « c’est ainsi que l’on change la signification d’un même objet en changeant la narration (narrative) dans laquelle il joue un rôle. » [7]

Ainsi c’est une histoire sans noms propres et sans chronologie qu’invoque Walter Benjamin. Une histoire qui ne peut se lire avec les outils habituels de l’histoire de l’art basés sur une évolution linéaire faite de gestes originaux. Voilà pourquoi chercher son origine est inutile. On constatera par contre que si elle n’a pas été initiée par une personne identifiable, elle l’a été par une technique, la reproduction, qui disqualifie l’originalité autant que l’« ici et maintenant » au profit du déplacement dans telle narration, dans telle exposition, sur tel support, dans tel contexte, qui toujours lui réinvente une inscription et une histoire.

- ↑ Nathalie Leleu, « Mettre le regard sous le contrôle du toucher. Répliques, copies et reconstitutions au XXe siècle : les tentations de l’historien de l’art », Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne, n°93, automne 2005, p. 85–103.

- ↑ Id., p.86.

- ↑ Id., p.86.

- ↑ Id., p.90.

- ↑ Inke Arns, « Les trous de ver de l’histoire de l’art », Trouble – Factographies, Paris, Trouble, 2010, p.127.

- ↑ Daniël Miller, « Interview with Walter Benjamin », A Prior Magazine, n°23, 2012, p. 44. Traduction de l’auteur.

- ↑ Beti Žerovc, « My dear, this is not what it seems to be : an interview with Walter Benjamin », Inke Arns et Walter Benjamin (ed.), What is Modern Art ? (Group Show) – Introductory series to the modern art 2, Frankfurt am Main, Revolver – Archiv fûr aktuelle Kunst, 2006, vol.2, p.30. Traduction de l’auteur.

Walter Benjamin: Histories of Works

This is certainly not the right moment to try and identify an origin. But because we have to start somewhere, let us take as our point of departure what would appear to be a beginning. It is in fact possible that the history of interest to us here started in 1986, in Belgrade and Ljubljana, where the “Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10” and the “International Exhibition of Modern Art” were held respectively. The former, organized by Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935), showed his famous Suprematist canvases, exhibited in exactly the same way as in the celebrated photo that records that same show put on in St. Petersburg in 1915-16. The latter was a copy of the Armory Show, whose subtitle it borrowed, the exhibition which introduced modern art to the United States in 1913.

Although these two projects involved different challenges and contexts, they did have certain points in common in that year 1986. Their titles, the works on view and the ways they were presented were similar to the exhibitions they were copying. The works shown in them did not, however, disguise the fact that they were replicas. Made in a rough and ready way, they basically looked like the original works, but without being faithful imitations. Judging from the photographs and writings recording those shows, it would seem that the objects presented were much more like signs referring to known works, thus representing reminders of past goings-on imported into the present, after undergoing one or two alterations due to those shifts in time.

That same year saw another resurrection, Walter Benjamin’s (1892-1940), as he gave a lecture in Ljubljana titled Mondrian ’63–’96. The actor playing the part of the philosopher presented an account of a corpus of paintings by Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) dated between 1963 and 1996. After questioning the nature of these works, he asserted that it was impossible to know who the author of those copies was, but that their dating and their style, which would never pass any authenticity test, suggested that they could not be the work of a forger. Walter Benjamin concluded that, in all probability, those paintings were destined to appear in a museum collection. They would duly be presented in the period tallying with them, the 1980s. If this was the case, a spectator following the chronology suggested in that place would be confronted by a strange phenomenon, a historical faltering calling into question the foundations on which that history was written. But above all he would have to conclude that he was dealing with two similar productions, issuing, however, from quite different intentions, to wit: two selfsame paintings with distinct conceptions.

Conférence de Walter Benjamin, Mondrian ’63 – ’96, Cankarjev dom, Ljubljana, 1986.

In addition to their dates having no connection with the art history we are acquainted with, what these three projects share in common is the fact that they present replicas in frameworks typical of the way the history of art of the 20th century was written. The expositions and studies of historians are in fact markers which underscore the appearance of such and such a paradigm, such and such a school, and such and such a line of thought, and, above all, underpin the chapters of a common history. The unfolding of this history is based on research into creative gestures which renew the genre and propose new ways of going about things. In a nutshell, it is a history which reckons that a new stage is reached every time an original and novel stance is identified.

Now, the projects of interest to us conversely propose copies. From their appearance, which does not camouflage their status and their dating, which is unconnected to that of the originals, the pieces shown in these projects are not called upon to stand in for the works they are imitating.

In our attempt to get to the bottom of the objectives involved, we might make mention here of the analysis made by Nathalie Leleu of the replicas which haunt certain museums [1]. In her text, the author looks into several re-creations of vanished and inaccessible works commissioned by museum curators. The people responsible for the copies of Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie (1943-1944) de Mondrian, reproduced in 1946 at the Stedelijk Museum, El Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet (1927-1928), re-created in 1968 at the Provinzialmuseum in Hannover, and Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919-1920), remade in 1979 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, were not forgers either. Their respective names were Willem Sandberg, Alexander Dorner and Pontus Hulten. They were guided by a single brief, to work with their favourite medium: the exhibition. In order to produce the narrative underpinning their praxis, they needed objects to present, and if the original was not available, a copy could stand in for it.

As Leleu explains, “If copies and re-creations take on the same symbolic function as the ‘authentic’ works they rub shoulders with in the exhibition space of the modern museum, their introduction into the collection—by way of the inventory, a normative and validating procedure—points to a break in the conventional spirit of the work of art, at the same time as a change of historical paradigm, of which these objects are the marginal but declared symptoms ” [2]. Otherwise put, in their desire to bring meaningful ensembles together, those responsible for writing art history through its display are opening up a Pandora’s box, the box of the copy, the box which denies the supremacy of the original gesture.

Leleu incidentally reminds us that, in the first lines of The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility, Walter Benjamin points out that “the artist’s replica, the copy, and the re-creation have always acted as auxiliaries of artistic creation, endowed with precise functions which vary from period to period” [3]. LThe function covered by the afore-mentioned re-creations is strictly educative, associated with the requirements of the exhibition. This means that their purpose is less to bear the name of their authors (Piet Mondrian, El Lissitzky and Vladimir Tatlin) than to act as examples illustrating the ideas of the curators commissioning them. These orphan-like works are not to be understood in order to detect therein an original creative gesture; rather, they appear as objects which are “open and reserved for the discourse and challenges of memory, over and above their substance” [4]. So it is no longer the artist and his work which are admired in this type of production, but the history which consecrates them as masterpieces.

Les Fleurs Américaines Une exposition conçue par / curated by Élodie Royer et Yoann Gourmel en collaboration avec / with le Salon de Fleurus, New York et le Museum of American Art, Berlin / Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau. Photo : Martin Argyroglo. 50 ans d’art aux États-Unis, collection du Museum of American Art, Berlin.

It is perhaps guided by a similar line of thought about the difference between a work seen as an object bearing the mark of its creator and its status as a historical icon that, in the “International Exhibition of Modern Art”, the style and making of the objects run counter to their typology of “authentic” production. Including the works of certain artists born after 1913, the exhibition presented, among other works, Joseph Kosuth’s Definition, an oil painting dated 1905, and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, in the form of a visibly handmade plaster sculpture.

In a less demonstrative way, all the paintings we can see in the three exhibitions which form “Les fleurs américaines” at Le Plateau are carefully executed but show styles well removed from those copied. In fact, by their explicit nature of being substitutes, they re-enact our relationship to art and its history since the invention of reproduction, since it is possible to see the works without going to them, but rather by getting them to come to us. In the slide shows and PowerPoint presentations used in art history courses, and in textbooks, all that are shown are replacements and stand-ins which have the features necessary for the demonstration which justifies their appearance, but not all the characteristics of the work being studied.

It is this history of exemplarity that runs throughout “Les fleurs américaines” in which reproductions of articles from newspapers, and photographs documenting this or that presentation of works are exhibited, shown in the same way as the paintings. Here, the history of presentation, through exhibition, historicization, and journalism is presented at the same level as the artist’s original gesture, which disappears a bit more in favour of a narrative. A narrative well underscored by the succession of the three projects brought together under the title “Les fleurs américaines”. It is written as a succession of three characters. The first is Gertrude Stein and her Salon de Fleurus, which was open in Paris between 1903 and 1913 and can be regarded as the first time modern works were brought together, and, for this reason, as the first stone in the edifice of the historicization of modern art. The second character is Alfred H. Barr, the first director of a museum dedicated to modern art, the Museum of Modern Art which opened in New York in 1929, where the first lines of a history and a typological classification of European modernity were written. The third person is Dorothy Miller who, with exhibitions such as “14 Americans” in 1946 and “Abstract Art in America” in 1951 extended that narrative and incorporated within it Abstract Expressionism, the movement that was then coming into being and was thus hallowed as a logical extension of that history.

The works thus become documents at the service of historical rationalization. The act of copying and re-creating which runs through “Les fleurs américaines” merely underlines this, as much as it demonstrates the way in which these documents have been used to write a history. Clad in this new status, the works actually no longer have as their author the person who produced them, but the person who shows them, the person who talks through them.

We are thus entitled to ask who the person is who produces such projects, who, under the overall name of Museum of Modern Art is presented as an “educational establishment” [5]. An educational project which, unlike those of curators, does not attempt to write a history but describe its construction. Here again, a ghost appears. In the same way as the narrator hides himself in the manipulation of works, the person who reveals how they function hides in anonymity and talks by bringing dead people back to life. The person who most frequently comes back is Walter Benjamin, often presented as the spokesman of the Museum of American Art.

In an interview, he explains that he no longer believes in art. According to him, “art exists only in ‘the story of art’, primarily as art history and art museums. And (I) don’t believe that it is an objective and universal story, but a simple invention of a certain kind of society” [6]. Now, this invention is based on respecting codes and parameters which validate its writing. With regard to the way in which this history is written, Walter Benjamin reminds us that for certain people believing in Christian history, a painting depicting a Madonna with child has these two persons as its principal figures. The same painting presented in a museum which, for its part believes in the history of art, will have as its main character the painter who executed it. Walter Benjamin concludes from this that: “This is how you actually change the meaning of the same object by changing the narrative in which it plays a role”. [7]

So what Walter Benjamin summons up is a history without proper names and without chronology. A history which cannot be read with the usual tools of art history based on a linear evolution made up of original gestures. This is why there is no point in looking for its origin. It can be noted, on the other hand, that if it has not been initiated by an identifiable person, it has been initiated by a technique—reproduction—which disqualifies the originality as much as the hic et nunc in favour of the shift in this kind of narrative, this kind of exhibition, this kind of medium and this kind of context, which invariably re-invent an inscription and a history for it.

- ↑ Nathalie Leleu, « Mettre le regard sous le contrôle du toucher. Répliques, copies et reconstitutions au XXe siècle : les tentations de l’historien de l’art », Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne, n°93, automne 2005, p. 85–103.

- ↑ Id., p.86.

- ↑ Id., p.86.

- ↑ Id., p.90.

- ↑ Inke Arns, « Les trous de ver de l’histoire de l’art », Trouble – Factographies, Paris, Trouble, 2010, p.127.

- ↑ Daniël Miller, « Interview with Walter Benjamin », A Prior Magazine, n°23, 2012, p. 44. Traduction de l’auteur.

- ↑ Beti Žerovc, « My dear, this is not what it seems to be : an interview with Walter Benjamin », Inke Arns et Walter Benjamin (ed.), What is Modern Art ? (Group Show) – Introductory series to the modern art 2, Frankfurt am Main, Revolver – Archiv fûr aktuelle Kunst, 2006, vol.2, p.30. Traduction de l’auteur.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Fulll Firearms d'Emily Wardill, The Otolith Group, Aurélien Froment, Oscar Tuazon à Vassivière, Guillaume Leblon,

articles liés

Biennale Son

par Guillaume Lasserre

Lou Masduraud

par Vanessa Morisset

Bharti Kher

par Sarah Matia Pasqualetti