Dirk Snauwaert

« Présenter l’actualité en art n’a jamais été notre préoccupation »

Le Wiels s’est installé sur un territoire alors vierge de ce qu’en France nous dénommons « centres d’art ». Il se définit comme n’étant « ni un musée, ni une Kunsthalle ou encore un palais des beaux-arts » mais comme « un laboratoire international pour la création et la diffusion de l’art contemporain ».

Aude Launay : Vous avez travaillé à sa conception pendant près de trois ans. Comment pense-t-on un tel projet ?

Dirk Snauwaert : Comme partout, il y avait à Bruxelles et dans ses environs des institutions et des lieux d’art contemporain de différentes tailles, de différentes formes d’organisation et soutenus par différentes formes de financement. Nous indiquons dans l’énoncé de notre mission qu’il y a des musées et des palais des beaux-arts, ce qui veut dire que c’est plus ou moins comme dans toutes les villes françaises : il y a des lieux d’art aux missions plus ou moins similaires ; la différence est qu’ici, ces lieux d’art ne sont souvent pas reconnus comme tels par l’ensemble de l’opinion publique artistique parce qu’ils sont orientés sur une « ethnicité linguistique » au lieu d’être empreints du plurilinguisme et de la transnationalité qui caractérisent le public et la citoyenneté de la région de Bruxelles. Notre première entreprise a donc été de rassembler et de comparer les missions culturelles et artistiques des différents pouvoirs publics et de voir comment le concept que nous voulions développer pouvait être soutenu par plusieurs de ces autorités, et comment ceci pouvait concorder avec le projet artistique novateur que nous avions qui cherchait à combiner la pratique artistique, les discours sur l’art, l’exposition, la pédagogie, la réflexion et la production. Pour nous, le programme de résidences internationales et son organisation inhabituelle a été un vecteur crucial, comme l’a été l’orientation de la programmation d’expositions qui se veut éclectique tant au niveau historique qu’au niveau des langages esthétiques et des personnalités des artistes invités. Présenter l’actualité en art n’a jamais été notre préoccupation car cet axe entraîne immédiatement des problèmes d’opposition générationnelle et aussi la nécessité de mesures d’adaptation du public aux nouvelles technologies. Nous ne souhaitons pas voir l’actualité comme un symptôme auquel il faudrait se conformer.

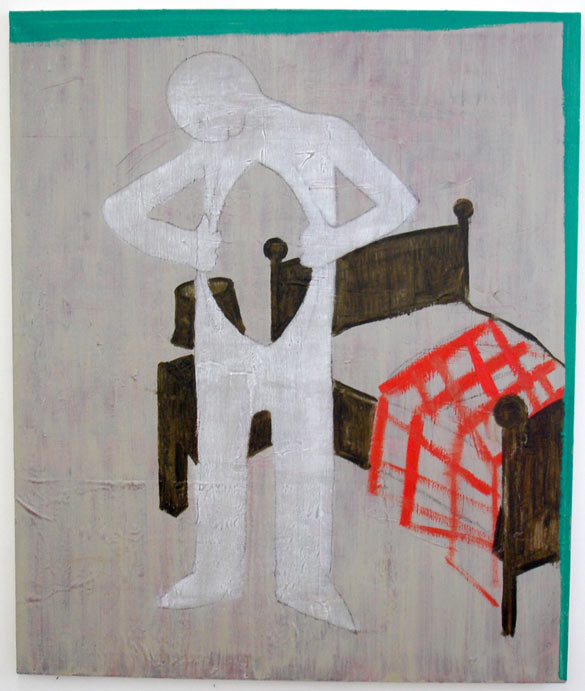

Jan Euler, Untitled, 2012. Vue de l’exposition / Installation view of ReSiDuE (21.06 – 01.09.2013), WIELS. Photo : Filip Vanzieleghem.

Vous évoquez le programme de résidences du Wiels et son organisation inhabituelle, pouvez-vous préciser ce point ?

D.S : Nous avons opté pour une « forme informelle » de réflexion et de dialogue plutôt que pour une forme de production et d’exposition. Le but n’est pas ici de « faire » une œuvre ou une exposition, mais de permettre aux artistes d’aiguiser le projet artistique qu’ils souhaitent développer.

Ce principe de résidences a été pensé par deux artistes internationaux expérimentés qui ont une bonne connaissance du territoire bruxellois, Willem Oorebeek et Simon Thompson. Ils accompagnent le groupe sur l’année, après avoir pris part à la sélection des artistes avec Devrim Bayar qui est la coordinatrice du programme. Ce programme est donc un peu comme un électron libre et perturbateur au sein d’une institution qui, autrement, risquerait de tomber dans l’enchainement d’une logique du calendrier des expositions temporaires.

Aviez-vous des modèles, des lieux d’art de par le monde dont le fonctionnement ou les orientations ont pu inspirer celui du Wiels ?

D.S : Nous nous sommes évidemment inspirés d’institutions pionnières, pour différentes raisons. Tout d’abord, j’ai toujours considéré l’ancien PS1, dans les années quatre-vingt et quatre-vingt-dix, comme un modèle très intéressant pour l’interconnexion de la pratique artistique et du milieu critique que constituaient les ateliers et les résidences internationales d’artistes et pour sa programmation d’expositions et d’interventions artistiques qui déjouaient le contexte du lieu et de son environnement, son passé et qui ne suivaient pas mécaniquement le flux de l’actualité qui se régénère en effets de mode permanents.

Un autre de nos modèles est le Power Plant, à Toronto, qui est aussi une institution avec un passé industriel qui a dû se réinventer en espace artistique prospectif et critique, avec également une programmation où expositions temporaires, résidences internationales, projets et pédagogie forment une interrelation dans une architecture particulière et rudimentaire.

L’orientation très peu formelle, dans une architecture très ouverte et robuste, que proposait le Palais de Tokyo à ses débuts a évidemment été aussi un exemple qui a nourri notre réflexion.

Walter Swennen, Konijn & canard, 2001. Huile sur toile / oil on canvas. Cera Collection/M-Museum, Leuven.

Aujourd’hui, après bientôt sept années d’existence, quels enseignements tirez-vous de cette expérience ; quelles sont vos satisfactions et vos déconvenues ?

D.S : Le moment de faire un bilan n’est pas encore venu, ce serait plutôt aux critiques d’art de le faire. Nous avons encore une partie du chantier à terminer, et j’espère que ce sera pour bientôt car ainsi nous pourrons compléter la diversité de notre programmation avec des conférences, des projections, etc., ce qui n’est pas encore possible dans des conditions satisfaisantes.

De mon point de vue, ma satisfaction est plutôt que, jusqu’à présent, nous n’avons pas dû faire de compromis, ni dans la programmation, ni dans l’encadrement, et que nous avons pu éviter l’engouement pour le tourisme culturel qui est de mise aujourd’hui.

Le modèle opérationnel et financier du Wiels a prouvé qu’il est possible de jumeler patrimoine et art contemporain, trois autorités publiques avec différentes orientations et un soutien massif de partenaires privés de la société civile.

L’une de mes frustrations reste la réticence avec laquelle les autorités francophones de la Capitale européenne s’engagent sur le plan des subsides. S’il s’engageaient autant que le font les Flamands, alors le projet ainsi que la culture à Bruxelles seraient en bien meilleure posture encore.

Walter Swennen, Inner, 2006. Huile sur toile / oil on canvas. Collection privée / private collection, BE. Courtesy Aliceday Bruxelles.

Quelle était la situation de Bruxelles à ce moment de la fondation du Wiels, la ville était-elle selon vous déjà un pôle d’attraction important pour les artistes et pour les galeries internationales ?

D.S : La situation n’était pas si différente de celle d’aujourd’hui car la « crise » s’est produite en 2007. Bruxelles, comme les autre villes et pays, a été fortement touchée par cette récession qui a aggravé de façon aiguë les problèmes économiques et sociaux de la population locale. Le milieu de l’art, qui se sent détaché de ces problèmes, s’est développé dans le même temps et avec une ampleur comparable à celle des institutions de la Commission européenne et à tout ce qui gravite autour, comme les lobbys européens ou ceux de l’OTAN. L’internationalisation a été dopée par la désignation de Bruxelles comme lieu unique des réunions du Conseil de l’Europe. L’attractivité de la ville est définie par cette internationalisation et par la présence de nombreux publics différents qui ont aussi fait que le clivage linguistique français-néerlandais semble de plus en plus inadéquat dans une capitale européenne. Une bonne situation immobilière avec pas mal d’habitat disponible, la proximité d’autres capitales artistiques et une nouvelle affluence de fortunes françaises font que, tout à coup, on pense que Bruxelles est un paradis pour l’art contemporain, mais ça reste à une échelle très modeste, vu les moyens publics qui ne sont pas très élevés, la complication d’institutions publiques et le fait que nous sommes tous confrontés à trois opinions publiques selon les groupes linguistiques, leurs coutumes et leurs zones d’intérêt.

In conversation with Dirk Snauwaert

“ Presenting the current state of things in art has never been our concern ”

The Wiels was set up in an at that time virgin territory of what we call “art centres” in France. It was defined as being “neither a museum, nor a Kunsthalle, nor a centre for fine arts” but as an “international laboratory for the creation and diffusion of contemporary art”.

Aude Launay : You worked on its conception for nearly three years. How does one think up such a project ?

Dirk Snauwaert : Like everywhere, in Brussels and its environs there were institutions and places of contemporary art of different sizes, with different forms of organization, and supported by different forms of funding. In our mission statement we point out that there are museums and centres for fine arts, which means that things are more or less the same as in all French cities: there are art venues with more or less similar briefs. The difference is that here, these art venues are not often recognized as such by artistic public opinion as a whole, because they are oriented towards a “linguistic ethnicity” instead of being imbued with the multi-lingualism and the transnationality which typify the public and citizenry of the Brussels region. So our first task was to gather together and compare the cultural and artistic missions of the different public powers-that-be, and see how the concept that we wanted to develop could be backed by several of these authorities, and how this could tally with the innovative art project we had in mind, which sought to combine art praxis, art discourse, exhibitions, teaching, reflection and production. For us the international residency programme and its unusual organization has been a crucial vehicle, as has the orientation of the exhibition programming, intended to be eclectic both at the historical level and at the level of the aesthetic languages and personalities of the artists invited. Presenting the current state of things in art has never been our concern, because this theme immediately entails problems to do with generational opposition, and also the need for measures to adapt the public to the new technologies. We don’t want to see the current state of affairs as a symptom with which we would have to comply.

You mention the Wiels residency programme and its unusual organization. Could you say a bit more about that ?

D.S : We’ve opted for an “informal form” of reflection and dialogue rather than for a form of production and exhibition. The aim here is not to “make” a work or an exhibition, but to enable artists to hone the art project they want to develop.

This residency principle was conceived by two practiced international artists with a good knowledge of the Brussels territory, Willem Oorebeck and Simon Thompson. They accompany the group over the year, after taking part in the selection of the artists with Devrim Bayar, who coordinates the programme. So this programme is a bit like a free and disturbing electron within an institution which would otherwise risk succumbing to a logic involving temporary exhibition timetables.

Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view of Walter Swennen: « So Far So Good » (05.10.2013 – 26.01.2014), WIELS. Avec / with: Chauve souris, 2001 ; Scarlett, 1998 ; Magic, 1998 ; Stark wie ein Stier, 2008. Photo: Kristien Daem.

Did you have models and art venues around the world whose operation and orientations inspired those of the Wiels ?

D.S : We’ve obviously drawn inspiration from pioneering institutions, for different reasons. First and foremost, I’ve always regarded the old PS1, in the 1980s and 1990s, as a very interesting model for the interconnection of art praxis and the critical milieu formed by workshops and international artists’ residencies, and for its programme of exhibitions and artistic interventions which thwarted the context of the place and its environment, and its past, and which didn’t mechanically follow the flow of current events which are regenerated as permanent fashion effects.

Another favourite model of ours is the Power Plant, in Toronto, which is also an institution with an industrial past which had to re-invent itself as a forward-looking and critical art space, likewise with a programme in which temporary shows, international residencies, projects and teaching all form an interrelation within a particular and rudimentary architecture. The very informal orientation, in a very open and robust architecture, proposed by the Palais de Tokyo in its early days was obviously also an example that nurtured our way of thinking.

Today, after what will soon be seven years of existence, what lessons do you draw from this experiment? What are your areas of satisfaction, and your disappointments ?

D.S : It’s not time yet to draw up a balance sheet, and that’s something that art critics should do. We still have part of the construction site to finish, and I hope that will happen soon because then we’ll be able to round off the diversity of our programme with lectures, screenings, and so on, something which is still not possible in satisfactory conditions. From my viewpoint, my satisfaction is rather that, up until now, we haven’t had to compromise, either in the programming or in the management, and that we’ve been able to avoid the craze for cultural tourism which is so “in” nowadays.

The operational and financial model of the Wiels has shown that it’s possible to combine patrimony and contemporary art, three public authorities with different orientations, and a massive backing from private partners in civil society.

One of my frustrations is still the reluctance with which the French-speaking authorities in the European capital become involved at the level of subsidies. If they were as committed as much as the Flemish authorities are, then the project and culture in Brussels would be in an even better position.

Vue de l’exposition / Exhibition view of Walter Swennen: « So Far So Good » (05.10.2013 – 26.01.2014), WIELS. Avec / with: Untitled (Les regardeurs), 1990 ; Inner, 2006. Photo: Kristien Daem.

What was the situation in Brussels when the Wiels was founded? For you, was the city already a major hub attracting artists and international galleries ?

D.S : The situation was not that different from today’s, because the “crisis” happened in 2007. Like other cities and countries, Brussels was greatly affected by that recession which acutely worsened the economic and social problems of the local population. The art milieu, which feels detached from these problems, developed at the same time and with a scope comparable to that of the European Commission institutions, and everything gravitating around them, like the European and NATO lobbies.

Internationalization was boosted by Brussels being designated as the only place where the Council of Europe held its meetings. The attractiveness of the city is defined by this internationalization and by the presence of lots of different kinds of public, which have also made the linguistic French-Dutch divide seem more and more incompatible in a European capital. A good housing situation with quite a bit of available accommodation, the closeness of other art capitals and a new wave of French wealth all mean that, all of a sudden, people are thinking that Brussels is a paradise for contemporary art, but this is still on a very modest scale, given the public funds, which are not very large, the complication of public institutions, and the fact that we are all confronted by three public opinions, based on the language groups, their customs, and their areas of interest.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : Paolo Cirio, RYBN, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner,

articles liés

Céline Poulin

par Clémence Agnez

Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

par Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Dena Yago

par Ingrid Luquet-Gad