Camille Henrot

Astute and inventive, Camille Henrot’s work has continued to develop through her examinations of nature and culture over the last decade. Coming from a background in film, Henrot has worked with a range of media, resulting in disparate forms that speak to the construction of culture. Her complex works often stem from extensive research and result in captivating images and objects. Her series of Ikebana works, Is it possible to be a revolutionary and like flowers?, uses the Japanese art of flower arrangement in response to famous book titles. Many of the books referenced, important political and philosophical tomes, are not necessarily considered in relation to the ornamentation of the flower arrangements. However, in Henrot’s interpretations, the book titles serve as scientific labels, ones you would come across in a botanical garden explaining the species of the plants you are viewing. The production of knowledge and its manifestations are highlighted through a presumed disjunction. In this series, as with many others, Henrot turns traditional taxonomies and classifications on their head. Often incorporating scientific means, botany or anthropology, Henrot disrupts straightforward interpretations, troubling associations with culture and gender.

Camille Henrot – « Robinson Crusoé », Daniel Defoe (série « Est-il possible d’être révolutionnaire et d’aimer les fleurs ? »), 2012 Installation: Techniques mixtes Dimensions variables Vue de l’exposition “Est-il possible d’être révolutionnaire et d’aimer les fleurs ?”, kamel mennour, Paris, 2012 © Camille Henrot Photo. Fabrice Seixas Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris.

In Objets Augmentés (2012), Henrot has collected various used and new household and recreational objects, such as a bicycle seat or a vacuum cleaner pipe, but she has reshaped them with clay and covered them in tar. Some of the objects are recognizable; while others become unfamiliar once their shapes are obscured or exaggerated and their surfaces tarred. Henrot’s act is like expedited fossilization: she simultaneously destroys the objects, as we know them, and ensures their future status as artifacts. This new taxonomy speaks to the types of objects we use and how they may be interpreted in the future, articulating the biases and misinformation that guides much of archeological past.

Camille Henrot – Objets augmentés, 2013. Installation : objets trouvés, enduits de terre et de goudron. Dimensions variables Vue de l’exposition “A Disagreeable Object”, SculptureCenter, New York, 2012 © Camille Henrot Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris.

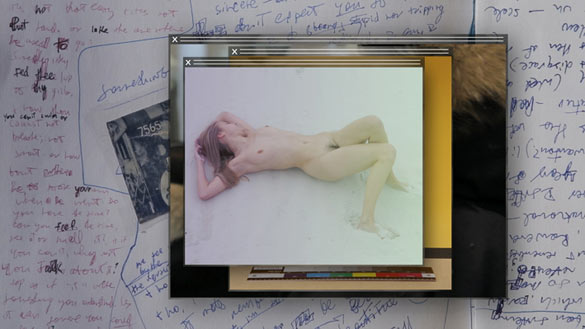

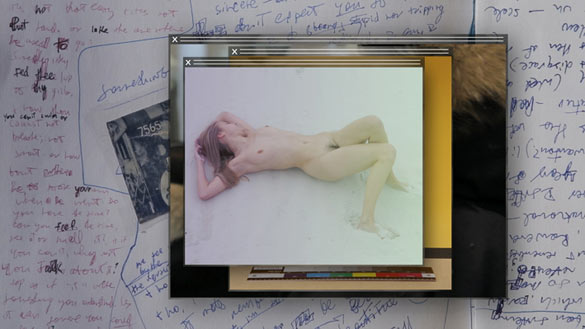

In her newest work, on view in the 55th Venice Biennale, Henrot similarly mines our past, present and future, ecstatically describing the origin of the universe as an event that is in constant formation, reinvented with every click of the mouse and every caress of an object, or body. The video was largely the result of a research fellowship awarded to Henrot at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. Her intensive research and time spent within the different museum within the Smithsonian resulted in Gross Fatigue (2013). Henrot doesn’t expound on the genus and species of the taxidermied animals pulled out of the Smithsonian’s archives, but we understand that they are part of cycle of life and regeneration that we are all subject to. Through the music, a ranting monologue (the voice of a man leads us through origin narratives), and images, the resulting work is a euphoric build up color, sound, and texture. Information is presented and quickly slips away into the ether, a demonstration of the ungraspable qualities around the creation of life, and the creation of knowledge. As in Gross Fatigue, Henrot’s works fearlessly tackle the largest questions, but do so with an energy and force that deliberately directs us into the labyrinth. Henrot consistently carves out distinct experiences through her works, ones that are clever and complex, but never dull.

Camille Henrot – Grosse Fatigue, 2013. Vidéo (couleur, sonore) / Video (color, sound), 13 min. Musique originale de / Original music by Joakim. Voix / Voice by Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh. Texte écrit en collaboration avec / Text written in collaboration with Jacob Bromberg. Producteur / Producer : kamel mennour, Paris ; avec le soutien du / with the additional support of : Fonds de dotation Famille Moulin, Paris. Production: Silex Films.

Film présenté dans le cadre de l’exposition / Film presented on the occasion of “Il Palazzo Enciclopedico (The Encyclopedic Palace)”, 55e Biennale de Venise / 55th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2013

Projet développé dans le cadre du / Project conducted as part of the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship Program, Washington, D.C.

Remerciements particuliers aux / Special thanks to: the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum © Camille Henrot – Courtesy the artist, Silex Films and kamel mennour, Paris.

articles liés

Patrice Allain, 1964-2024

par Patrice Joly

AD HOC

par Elsa Guigo

Bivouac, après naufrage

par Alexandrine Dhainaut